It is Monday evening on the ground floor of the adult psychiatry ward in Kirchberg. A young patient has just been admitted for acute anxiety attacks and the nurse accompanies her to her room: “You’re lucky, you’re sharing the room with a girl your own age, she also arrived today.”

She enters the room and Letizia is sitting on her bed by the window. The nurse has just left and the two girls start to get to know each other: “Why are you here?”, asks Letizia, to which the other patient replies that she is also having anxiety attacks. “Welcome to the club”, replies Letitzia and both start laughing although the situation is not really that funny.

Letizia was eleven when she started having anxiety attacks, which at the time were still relatively harmless compared to the ones she is having now. In addition, she developed an eating disorder and lost a lot of weight. Her family took her to several doctors who all said it was anorexia.

Around the same time, Letizia’s parents were getting divorced, which caused her anxiety attacks to worsen and she eventually began harming herself. She was hospitalised for the first time at the age of 13 and put under supervision in a psychiatric clinic: “I knew there was something wrong with me, but no one was able to tell me what it was. And this continued almost until I was 20. Most of the doctors told me it was depression as this condition was already known in the family. And so everyone assumed it was genetic and no one tried looking further.”

As she grew older, her problems increased and her anxiety attacks became stronger and more regular. But at school, Letizia continued being a good student and often fooled around in class, although things were constantly getting worse at home. Mood swings would appear from one minute to the next and become a common companion.

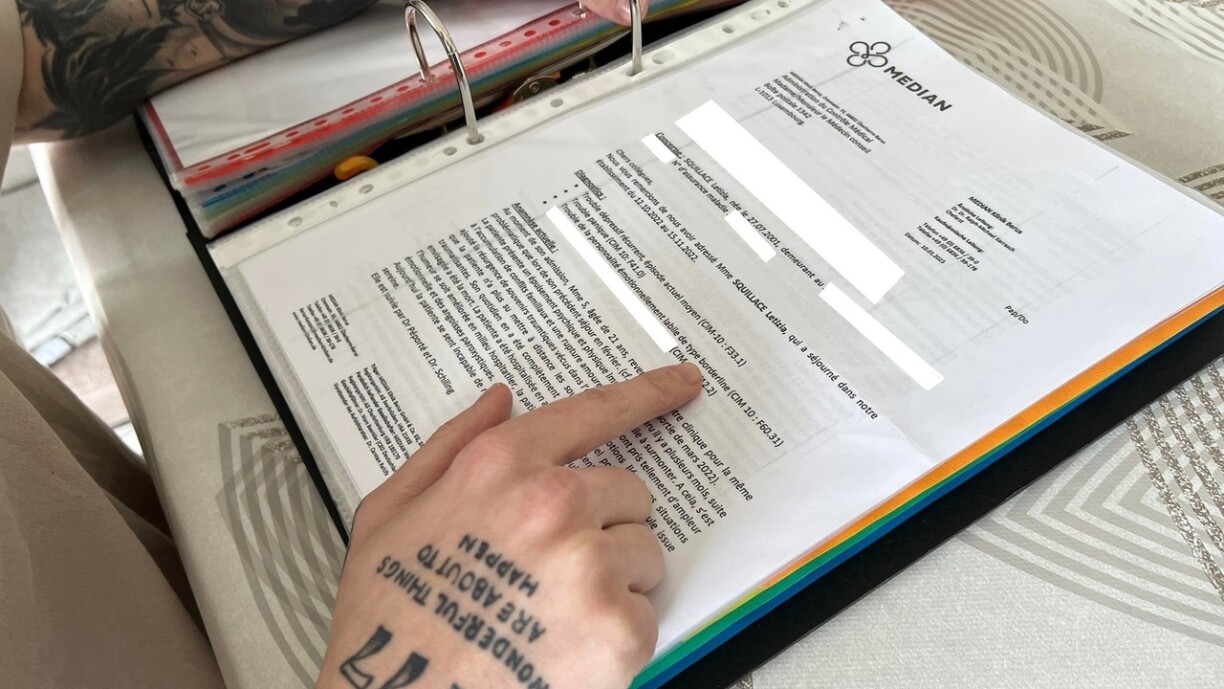

A little over a year ago, her anxiety attacks reached such a high level that she was almost paralysed, unable to feel her body. She finally underwent therapy at a German clinic where she discovered at the age of 20 years and nine months that she had a borderline personality disorder. At first it was a great relief: “At last I knew what I had. It has a name. And then a lot of questions were running through my mind, what is it? Will I be able to get rid of it?”

“Everything is black or white, everything is very beautiful or very very ugly. There are no shades of grey. There’s nothing in between,” says Letizia. This personality disorder is mainly characterised by extreme mood swings, instability, and hypersensitivity. Letizia always has an extreme fear of loss in her relationships, she idealises people, and has the need to please everyone at all costs.

When a cancellation is made at the last minute, her emotions sometimes cause her to have anxiety attacks. People with borderline personality disorder can experience an uncontrollable “emotional storm” following the smallest event in their lives. The emotions Letizia feels can sometimes be so strong that her body no longer responds. During these moments, Letizia has already hurt herself or even contemplated taking her own life.

Impulsivity plays an important role in her life, she can book a flight at the drop of a hat and leave the next day without warning. People might think she is a super spontaneous person, but there is an important difference as she does not consider the consequences of her actions in these impulsive moments and sometimes gets into complicated or even dangerous situations. It is only later that she is taking a step back and will ask herself why she did it, but then it is usually too late. Impulsive and impatient, she knows she is making risky decisions, but does not realise it at the time.

The diagnosis helped Letizia understand why she is like that, which helps her to better manage those impulsive moments or emotional storms. But, a diagnosis alone is not enough, at 21 she already has to take a whole series of medications to stabilise her disorder after several therapies when she was younger.

In 2016, she was already in stationary psychiatric care before moving abroad to specialised clinics and eventually returning back to adult psychiatric care in Kirchberg. However, all these treatments did not help Letizia get better and although she came to terms with her personality disorder, she still often goes from one extreme to the other.

She continues her struggle with a lot of self-help and would like to follow a dialectical behavioural therapy, a method often used for patients with borderline personality disorder, as well as for people who suffer from chronic suicidal behaviour.

Unfortunately, it is not easy finding a place in these therapies. Offers exist in Luxembourg, but most are only for young people up to the age of 18. Letizia has abandoned public clinics abroad and private institutions are too expensive, even if the costs are partially covered by the National Health Fund (CNS). One still has to pay a considerable amount of money before one is reimbursed and €500 a day for a stay of up to two months is not feasible that way.

Her supplementary health insurance refuses to pay for these therapeutic stays because she already went through psychiatry in 2016 and this violates the obligations. Other health insurances do not accept her as a client because her file is too costly. So, she has to pay for part of her medication, which the CNS does not reimburse and which is €50 every two to three weeks.

A clinic in Aachen, Germany, might be able to take her in after a first presentation appointment, as might a hospital in Munich, but only from October onwards. “Everything is taking a very long time and I’m wasting a lot of time, plus I’m only entitled to unemployment until September and I’d like to go back to work, but the longer the therapy takes, the more I have to postpone all my plans”, lements Letizia.

However, Letizia benefits from the status of a disabled person, and even if it is a kind of label that is stuck to her skin, it still reassures her: “When I go to work, my boss knows my situation, he is informed about it and knows very well why it is not going well at all, that takes the pressure off me. And if things don’t work out, I can still go and work in a sheltered workshop, that’s another solution.”

There are times when Letizia curses her personality disorder because it makes her life complicated and exhausting, but having borderline personality disorder is also part of her life. Despite the challenges it brings, there are positive aspects to being borderline, such as making her more open and motivated to discover and explore anything she wants.

The 21-year-old is now giving her all to her modelling career, but she also sees herself working as a media presenter.

Letizia has no problem talking about her personality disorder as it is part of her character: “I don’t hide it, but if I meet someone, it’s not the first thing I’ll mention. It’s part of my daily life and it’s never going to go away. All I can do is learn to deal with it better and live with it.”

This applies to many mental illnesses and personality or behavioural disorders. One has to accept it and learn to build a life around it to live better with the disadvantages, but also the advantages that come with it.

People with suicidal thoughts can get help from the SOS helpline on (+352) 45 45 45 or online at www.prevention.suicide.lu.