A co-production between Iran, France and Luxembourg, the film is the latest offering to highlight the Grand Duchy’s growing role in international cinema.

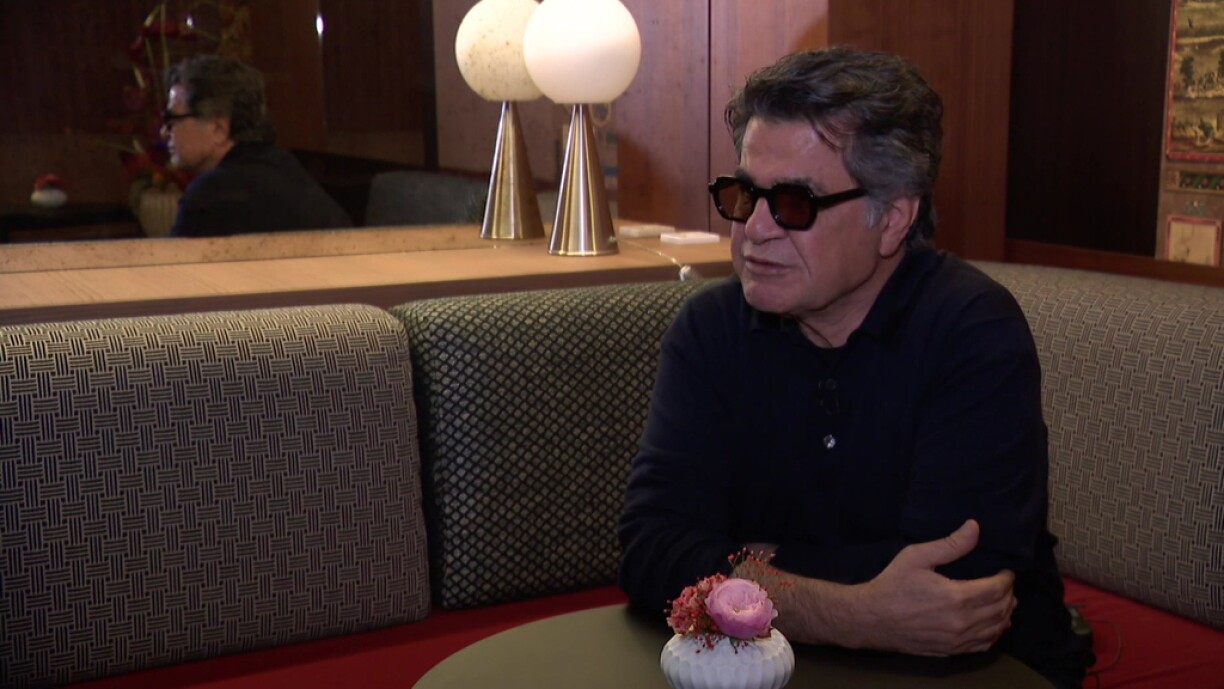

Next year, the film by Jafar Panahi will also represent France in the race for the Oscar for Best International Feature. The director is known for his ability to provoke thought and laughter even when tackling dramatic themes. In an interview, he reflected on his work, the challenges of making critical cinema in Iran, and the lessons to be drawn from it.

Panahi has long received international awards for films he was not allowed to shoot officially, and for prizes he could not collect in person. His works often depict realities that Iran’s clerical regime forbids, such as his film The Circle, which portrays the oppression of women and was condemned as propaganda.

At Cannes, however, the country’s best-known filmmaker was finally able to accept the Palme d’Or himself. Less than 24 hours later, he returned to Tehran, where the reception was mixed: he was greeted at the airport by fellow filmmakers, friends, family members, and even political prisoners, while the authorities dismissed the prize as purely political and banned the film from being shown in Iran, a fate that applies to all critical directors.

Panahi acknowledged that his films are inherently political, but emphasised that above all he is a filmmaker. As a symbol of resistance, he refuses to go into exile, he said. For him, living outside Iran has never been an option, as he has always lived there and intends to continue doing so.

That choice comes at a high cost. In Iran, engaged cinema is punished with imprisonment. Panahi was sentenced to six years, served eight months in detention, and was only released after going on hunger strike. He explained that while ordinary prisoners who go on hunger strike might go unnoticed, his protest drew global attention. He noted that international recognition and awards bring him visibility, which can serve as protection, but can also expose him to further danger.

The idea for It Was Just An Accident emerged during his time in prison. The film tells the story of a man who unexpectedly encounters his former torturer and recognises him only by his voice, since prisoners were blindfolded during interrogations involving torture. The central question is how to respond and how to preserve one’s humanity in the face of such experiences.

For Panahi, this is a universal issue. Cinema, he explained, is often described as a universal language because, despite cultural differences, audiences everywhere can recognise themselves in such questions. His film explores problems we all share: how to break the cycle of violence, a question that arises after every conflict, he said.

He also stressed that the film is set before the fall of a regime rather than after. Usually, such stories are told in hindsight, as was the case in Europe after the Second World War when collaborators were confronted, he said. Here, however, he raises the question in anticipation of change.

Panahi still hopes for such change in Iran, wishing to believe that the regime will eventually fall and violence will end. Yet he also warns that, globally, the law of the strongest seems to prevail. He recalled that after being banned from travelling for 17 years, he now sees a world moving in a dangerous direction.

At the Toronto Film Festival, he noted, a journalist whispered questions out of fear of being overheard. According to Panahi, those who have lived through such repression recognise the warning signs and know how events can unfold if unchecked.

It Was Just An Accident will open in Luxembourg cinemas on Wednesday, 1 October.