After the United States, Argentina was the country to receive the most European immigrants, especially of Germanic and Italian origin. The nineteenth century was above all characterised by great waves of migration, both to and from Europe. And of course, Luxembourgish populations were also on the move, emigrating notably to France, the United States, and South America.

When we think of European migrants settling in South America, we usually tend to think of Italians and Germans, who often moved there prior to industrialisation. However, Luxembourg also saw significant amounts of its population leave for the New World, which is all the more impactful given how small the country was.

Find out more about Luxembourg’s pioneers in this podcast episode:

Nicolas Gonner, a nineteenth century writer and historian who ultimately ended up settling in Iowa, extensively documented the Luxembourgish exodus to the new World, and attributed migration predominantly to the personal union of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg with the United Kingdoms of the Netherlands, as agreed at the Congress of Vienna.

Gonner described the union as an unhappy one, as it severely neglected the interests, the rights, the religions, and the traditions of all the different nationalities grouped together in the union. Whilst economically, the United Kingdoms and the Grand Duchy experienced progress, this was accompanied by a massive increase in taxes. The Luxembourgish people especially suffered as a result of the taxes, given that agriculture was the reigning occupation in early nineteenth-century Luxembourg (80%) and one of the most hated taxes was the tax on meal.

Further to that, much of the population was poor by 1847, perhaps a consequence of the country’s boundaries shrinking to their present dimensions in 1839. As a result, part of the population began moving to other countries. Between 1840 and 1890, 66,000 left Luxembourg, perhaps an insignificant number for other European countries, but representing a large portion of Luxembourg. The Grand Duchy’s population ranged from 175,000 in 1839 to 210,000 in the 1880s.

The Luxembourgish population shift to the Americas can be split into four movements: the first two emigration waves went to Brazil, the next saw Luxembourgers join a Belgian colonial expedition to Guatemala, and finally, Luxembourgers also formed part of the migration shift to Argentina. More specifically, we should say the first two waves endeavoured to go to Brazil, but were not all too successful.

Of all the South American-bound movements, the first three took place in the first half of the nineteenth century and the Brazilian ventures were far from successful. In the 1820s, Luxembourgers joined German migrants in an endeavour to reach Brazil not long after the state had become independent from Portugal as its own empire. More than 2,500 Luxembourgish peasants joined the move in 1828, but two-thirds of these so-called Brazilian travellers (Brazilienfahrer) never even made it across the Atlantic.

In 1828, the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro I, announced that no more European immigrants would be allowed to enter Brazil. A group of around 100 Luxembourgers, who had sold everything they owned in Luxembourg with hopes of emigrating, arrived in Bremen only to find they couldn’t board a ship to Brazil.

Victims of dishonesty and robbery, many of these families returned from the transatlantic journey before even leaving Europe. Perhaps shunned by their original communities or too proud to return, they established a new settlement called “New Brazil,” now known as Gréiwels. The Luxembourg government resettled them in the area known as “Um Kale Räis,” at the boundaries of the municipalities of Grosbous, Heiderscheid, and Wahl. The villagers were so impoverished that they resorted to stealing potatoes from neighboring farmers to survive.

The second attempt to move to Brazil, some twenty years later, similarly found its end at Dunkirk in France. Whilst half of this smaller migration did again return to Luxembourg, the other half selected a new destination – Algeria. Nevertheless, a very small community from the 1828 expedition did arrive in Brazil and established a village named Lussemburgo in the Espírito Santo province. Some families today can still trace their roots back to Luxembourg, with an estimated 50,000 Brazilians having partial Luxembourgish descent.

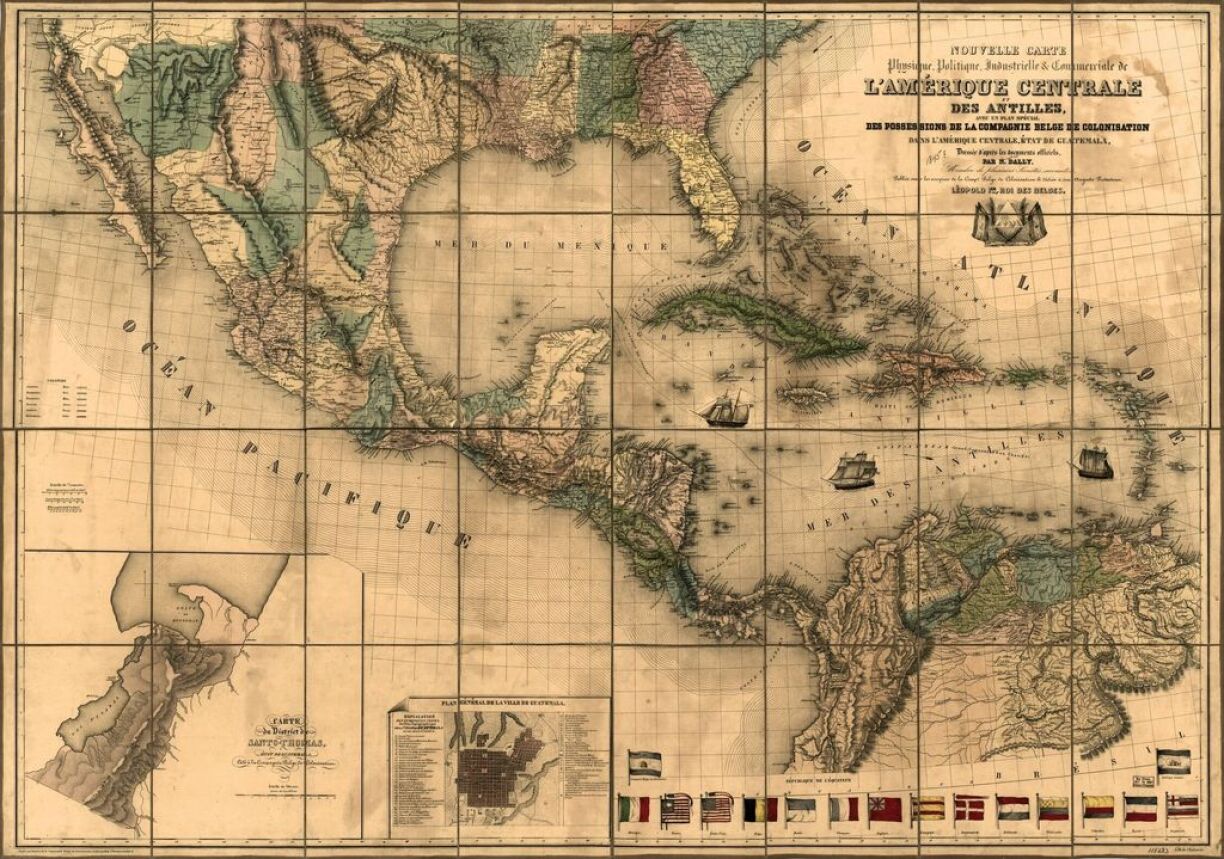

Luxembourgers often joined their Belgian neighbours in their colonial ventures, in this case, an attempt by the Belgian state to found a settlement in the most isolated part of Guatemala. The expedition began in 1842 and its purpose was to take advantage of Guatemala’s agricultural and natural resources to the benefit of the Belgian state alongside creating a colonial urban settlement. Supported by King Leopold I (not the nasty one, that’s Leopold II), investors set up the ‘Compagnie belge de colonisation’.

Given the company’s publicity and public support from Belgian social elites, both Luxembourgers and Germans joined as potential emigrants to Santo Tomás de Guatemala. Only several hundred Luxembourgers were enticed by potential riches – and severely disappointed as the Belgian attempt in Santo Tomás faltered. There are no historical findings confirming a Luxembourgish exodus back to the homeland, but Luxembourgers may have returned to Europe thanks to shipping routes to Antwerp.

So in conclusion, the three first migration waves to South and Latin America were certainly not as successful as the North American emigration. The move to Argentina did prove more successful.

Thank you for tuning in! Now what are you waiting for – download and listen, on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathalie Lodhi was an editor and translator for RTL Today with a background in history.