In the rolling hills of northern Luxembourg, far from the frontlines but deep inside occupied territory, a young farmer became one of the country’s most daring resistance figures. Pierre Schon, just 25 years old when the Nazis invaded, lived in the small village of Doennange near Clervaux. He worked on the family farm and, almost immediately, began working for something far greater.

Pierre joined the newly formed Luxembourgish Patriot League (LPL) North resistance group in November 1940, the month it was created. From that moment until the end of the war, he operated as a group leader, intelligence liaison officer, and an escape guide who led more than a hundred people to freedom through the dangerous terrain in Nazi-occupied Europe.

The Schon family home became both a meeting point and a refuge. Resistance members such as Raymond Petit found shelter there. So did escaped French prisoners of war, downed Allied airmen, and young Luxembourgers desperate to avoid forced conscription into the German army. Pierre and fellow LPL members built secret hideaways in the woods between Doennange and Weicherdange, where escapees waited before being escorted to safety to Belgium through the forest routes under the cover of darkness.

The escape route linked Doennange to Belgian villages Buret and Tavigny and on to small towns with railway connections such as Limerlé-Retigny and Bourcy. Pierre worked closely with fellow escape guides Ernest Delosch and Aloyse Kremer, setting up safe houses and coordinating handovers with Belgian families.

His Belgian network proved indispensable. Families like that of Jean Boever near Marloie fed, clothed, and sheltered escapees, even cutting up their own tablecloths to make shirts for them. Boever established a network of other courageous local families who also hid large numbers of escapees. René Nicolay, head of the Marche gendarmerie, provided forged identity and work cards, along with food and funds. Together, this cross-border collaboration saved hundreds of lives.

Pierre possessed the tools and skill to forge identity documents himself. He had original municipal stamps from France and Belgium. He provided some of these forged papers to help Jewish deportees escape from the convent camp at Cinqfontaines, with the intention to take them over the border to Belgium.

False identities also enabled resistance members to travel across the region without detection. Larger numbers of forged ID cards were produced in coordination with Belgian resistance contacts, a system that grew more important as the war progressed.

During the forced Nazi referendum, the “Personenstandsaufnahme” in October 1941, he helped distribute anti-referendum pamphlets printed in Brussels and organised by LPL cofounder Alphonse Rodesch. Circulated by members like Pierre, these leaflets contributed to Luxembourg’s overwhelming rejection of the German plan to annex the country. He played a similar role during the General Strike of August 1942, smuggling pamphlets across the border and helping distribute them with other resistance groups. He later collected money for the families of those arrested.

In February 1943, Pierre undertook what may have been his boldest mission. Using a completely false identity, he travelled across Nazi Germany to Silesia to deliver more than 1,000 kilos of provisions to deported Luxembourgers held at the Boberstein resettlement camp. The Polish government later awarded him a medal for his humanitarian assistance.

But the risks were relentless. By April 1943, with his name circulating on the Gestapo wanted list for anti-German activities and immediate arrest, Pierre was forced to flee across the border into Belgium where he continued his work from the other side of the border. Recruited by Luxembourger Jules Dominique head of the Brigade du Lion Rouge, Pierre officially joined the Belgian resistance on 15 May 1943 as a member of Les Insoumis.

In 1944, he was persuaded to lead a maquis – a guerilla forest unit of 20–30 Luxembourgers, hidden in the dense woods near Lavacherie. Trained in explosives by the British Special Operations Executive, Pierre and his unit carried out sabotage missions aimed at disrupting German troop movements and supplies ahead of and during the Allied invasion.

Dominique later described Pierre to the Belgian authorities as “an excellent escape guide and resistance fighter” who had repeatedly carried out daring armed attacks on convoys, rail lines and communication routes near Bande and Amberloup to contribute directly to the Allied campaign and the liberation.

Pierre and his network helped bring nine downed allied pilots to safety.

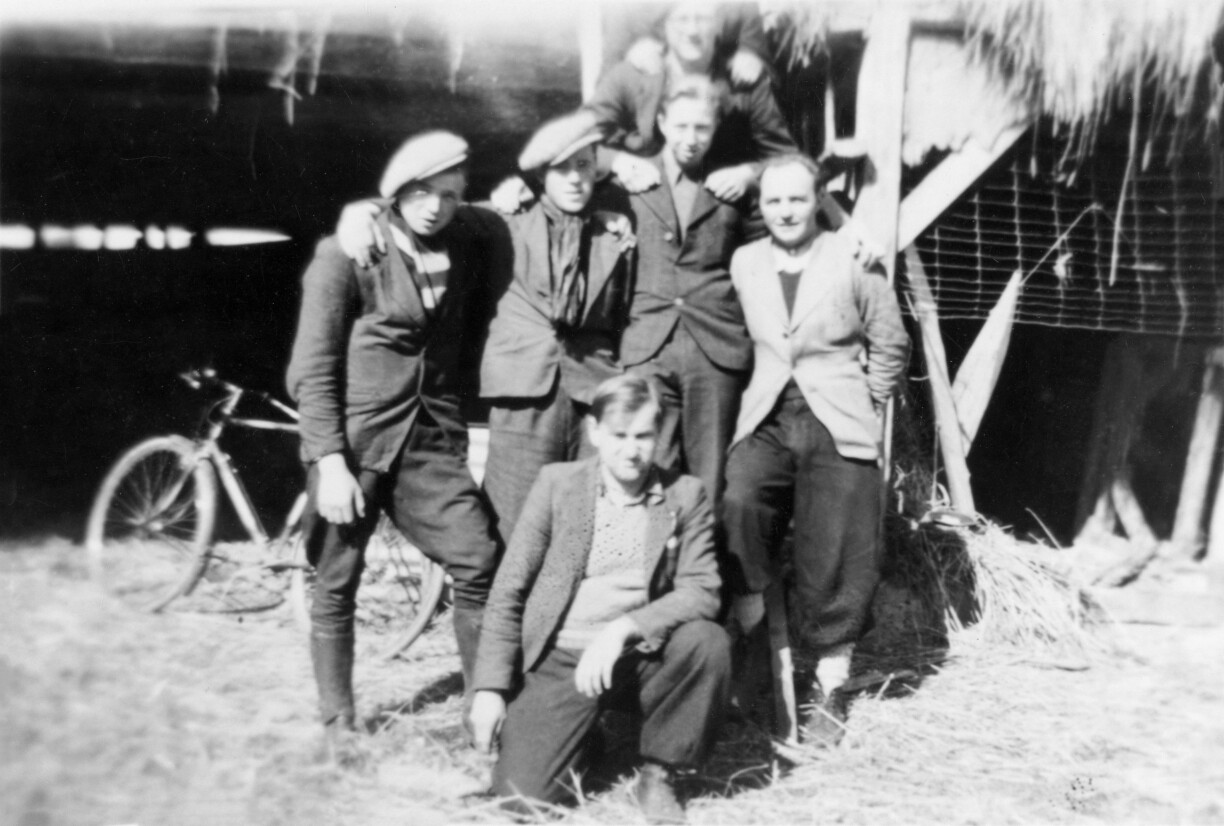

In June 1944, together with other LPL members, Pierre met two British pilots and one Canadian at the Luxembourg–Belgium border, supplying them with forged identities and funds before transferring them to the Maquis du Lion Rouge. A group photograph (below) captures the moment these men – airmen, resistance fighters, refugees – arrived safely together at Limerlé station for the next stage of their journey.

After Luxembourg’s liberation in September 1944, Pierre briefly returned home. However, the German counter-offensive in December forced him to flee once more. He helped the US Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) by guiding Luxembourgish refugees to safety to Belgium and helping them secure paperwork to return once the front had stabilised.

In the post-war years, he dedicated himself to refugee relief, becoming a key figure in both civilian and military support centres.

He also participated in the identification and arrest of collaborators, work made more personal by the memory of his close friends Aloyse Kremer and Ernest Delosch, both arrested, tortured by the Gestapo and executed for their escape-line activities.

Awards and commendations came from Luxembourg, Belgium, France, Poland, Commonwealth of Nations and the United States, including a certificate signed by General Eisenhower.

However, the greatest testament to Pierre Schon’s legacy remains the lives he saved and the courage he displayed, constantly putting his own life at risk for over four years to help others.

To explore his full story, visit www.pierre-schon.lu (in English, French, Luxembourgish, and German). A book is also available on Amazon.

Sue grew up in England and, after completing her studies, spent three years in Germany and 26 in Belgium before moving to Luxembourg in 2009 with her partner, François Schon, Pierre’s son. A lifelong history enthusiast, she began researching and documenting Pierre’s story after the 80th anniversary of the liberation, determined to preserve such histories and honour the sacrifices made for freedom.

Sue recalls hearing her parents speak of air raids and food shortages during the war, yet the United Kingdom remained free. Through this research, she came to grasp how unimaginably hard life was under Nazi occupation. Pierre’s story is just one of hundreds still waiting to be told. Sue encourages descendants of resistance heroes to uncover and pass on these stories – and to share them with the Museum of the Resistance, an important place to preserve this legacy.