The images went viral worldwide. Acting with striking confidence and precision, the gang managed to vanish with priceless treasures before two members were eventually arrested. The loss, however, went far beyond financial value, as it was a blow to France’s heritage. The jewels, once part of Napoleon’s collection and displayed in the Louvre’s famed Apollo Gallery, have completely disappeared.

Art recovery expert Christopher Marinello, founder of Art Recovery International, explained that the chances of retrieving stolen art are slim, and even lower when it comes to jewellery. He cited cases like the gold toilet stolen from Blenheim Palace or the jewel theft at Dresden’s Royal Palace, where the thieves were caught but the artefacts themselves were never recovered, as they are usually dismantled or sold off rapidly.

In the case of the Louvre jewels, investigators suspect the pieces were taken apart in Antwerp or Tel Aviv, both known hubs for the diamond trade, making resale possible. Marinello stated that such a high-profile theft could inspire copycat crimes.

Marinello described the theft as a brazen act in one of the world’s most prestigious museums, adding that it was an affront to every museum, but also a wake-up call. Institutions holding valuable gold or jewellery, he warned, should be reviewing their protection measures.

Luxembourg’s museums are no exception. Bettina Steinbrügge, director of the Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (MUDAM), explained that she happened to be in Paris at the time and spoke with several museum directors about security standards: what is required, how emergency plans work, and how to respond in a crisis. She noted that such events naturally prompt internal reviews of protection measures.

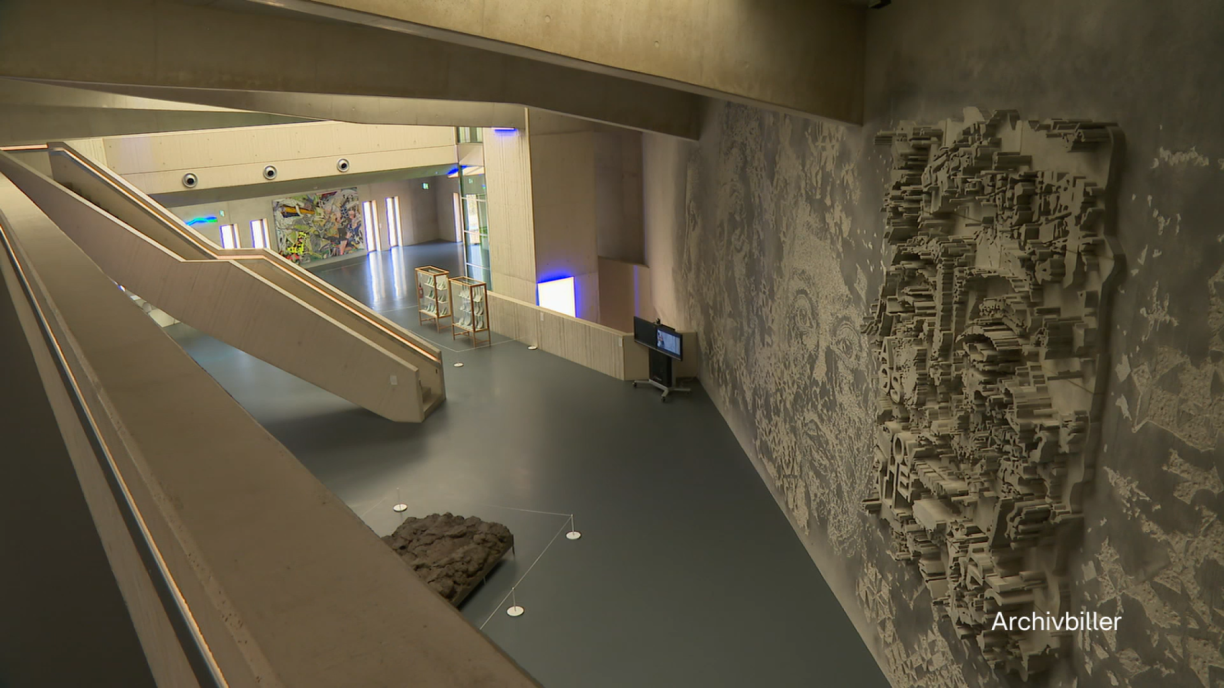

From the outset, the MUDAM invested heavily in advanced security systems, she said. Although no system can ever be infallible, Steinbrügge said the museum takes every possible precaution, stating that as a relatively young museum, they operate with very high standards, from surveillance and alarms to personal security. She highlighted that they also have detailed emergency procedures that are reviewed annually.

Luxembourg also benefits from a key asset: the High Security Hub at Findel Airport, where some of the country’s most valuable artworks are stored. The facility offers not only ideal conditions for art conservation but also the highest level of protection against theft. Steinbrügge called the High Security Hub the best storage site in Luxembourg, built to the highest standards.

Yet one philosophical question remains: what value does art retain when it is hidden away behind reinforced walls? When paintings, sculptures, or relics are no longer accessible to the public, do they not lose their cultural purpose, becoming mere financial assets rather than shared heritage?

Reflecting on the Louvre’s decision to move its royal jewels into a vault, Steinbrügge observed that museums constantly struggle with this balance. She explained that, on one hand, they wish to display their treasures, but that they also have to recognise that risks, ranging from theft to natural disasters, can never be fully eliminated. She concluded that a museum’s duty is to minimise those risks, while acknowledging that absolute safety does not exist.