In a 2015 interview with Paperjam, French language expert Frank Wilhelm noted that in the 19th century, “French was the instrument or means of expression for Luxembourg’s post-revolutionary bourgeoisie, including liberal professionals, senior civil servants, and merchants.” He suggests that this association may have alienated parts of the working class, for whom French remained a “foreign” language—though Wilhelm prefers to call it a “second language.”

Despite its status as one of Luxembourg’s official languages, French has seen its prestige wane. Once central in the Chamber of Deputies until the 1984 language regime law, and heavily promoted by RTL Télévision in the 1970s and 1980s, French no longer enjoys the same affection.

Factors such as nuclear reactors on the French side of the border, French criticism of Luxembourg’s tax practices, and perceived arrogance from some cross-border workers have contributed to a decline in the language’s popularity, even though it remains widely used in the workplace.

In the aforementioned article, Frank Wilhelm observed that “younger generations are less sensitive to French cultural achievements, the French spirit, irony, and the ritual questioning of facts and thoughts, and are instead drawn to German seriousness and reliability.”

Tonia Raus, head of the master’s programme at the University of Luxembourg for future secondary school French teachers, offers a more balanced perspective: “It seems we’ve been grappling with this issue for generations […] I’m not convinced that there’s a true crisis regarding the French language. However, we must acknowledge the challenge in Luxembourg of sequential literacy—first in German and then in French—which can sometimes overwhelm students and parents.”

The Ministry of Education has decided to react to what Christiane Bechtold, a coordinator at the Ministry, describes as “a decline in motivation to learn French during the schooling of certain pupils.”

This decline is reflected in some telling statistics. Data from the Ministry’s school monitoring shows how comprehension of written French has shifted in 5th-year classes (third year of secondary school in the Luxembourgish system). In 2010, 29% of students were in the group categorised as below level 1, with the remaining 71% assessed at levels 1 to 4. By 2023, the proportion of students in the below level 1 group had increased to 36%.

In response to these trends, the 2018 coalition agreement initiated a comprehensive reform of French language education, including the development of new teaching materials.

The Ministry collaborated with the Paris-based publishing house Clé international and assembled a task force of teachers familiar with Luxembourg’s unique linguistic environment. Scientific guidance was provided by Jean-Louis Chiss, Emeritus Professor of Language Science and French Didactics at the Sorbonne, and Evelyne Rosen-Reinhardt, Senior Lecturer in French Didactics at the University of Lille.

The outcome is the creation of three series of textbooks for cycles 2, 3, and 4: Salut, c’est parti!, Salut, c’est magique!, and Salut, c’est à toi! These textbooks are accompanied by teaching guides, worksheets, games, and even QR codes that provide access to a variety of audio content, such as readings, recordings, and songs.

“We often hear that children are less afraid to speak French,” notes Christiane Bechtold. She explains, “We offer active, fun learning through games, which helps remove the fear of making mistakes and encourages children to speak up. The materials include numerous examples where children interact, communicate, and role-play. They learn many things in French that they can apply to concrete, motivating tasks relevant to their lives as children.”

To better address the linguistic diversity of the school population and tackle educational inequalities, the Luxembourg government has launched the Zesumme Wuessen! literacy pilot project in four primary schools. This project allows C2.1 pupils to begin learning to read and write in either French (ALPHA-French) or German (ALPHA-German) in mixed classes. An analysis of the project’s initial results last June revealed higher levels of general motivation and well-being among students.

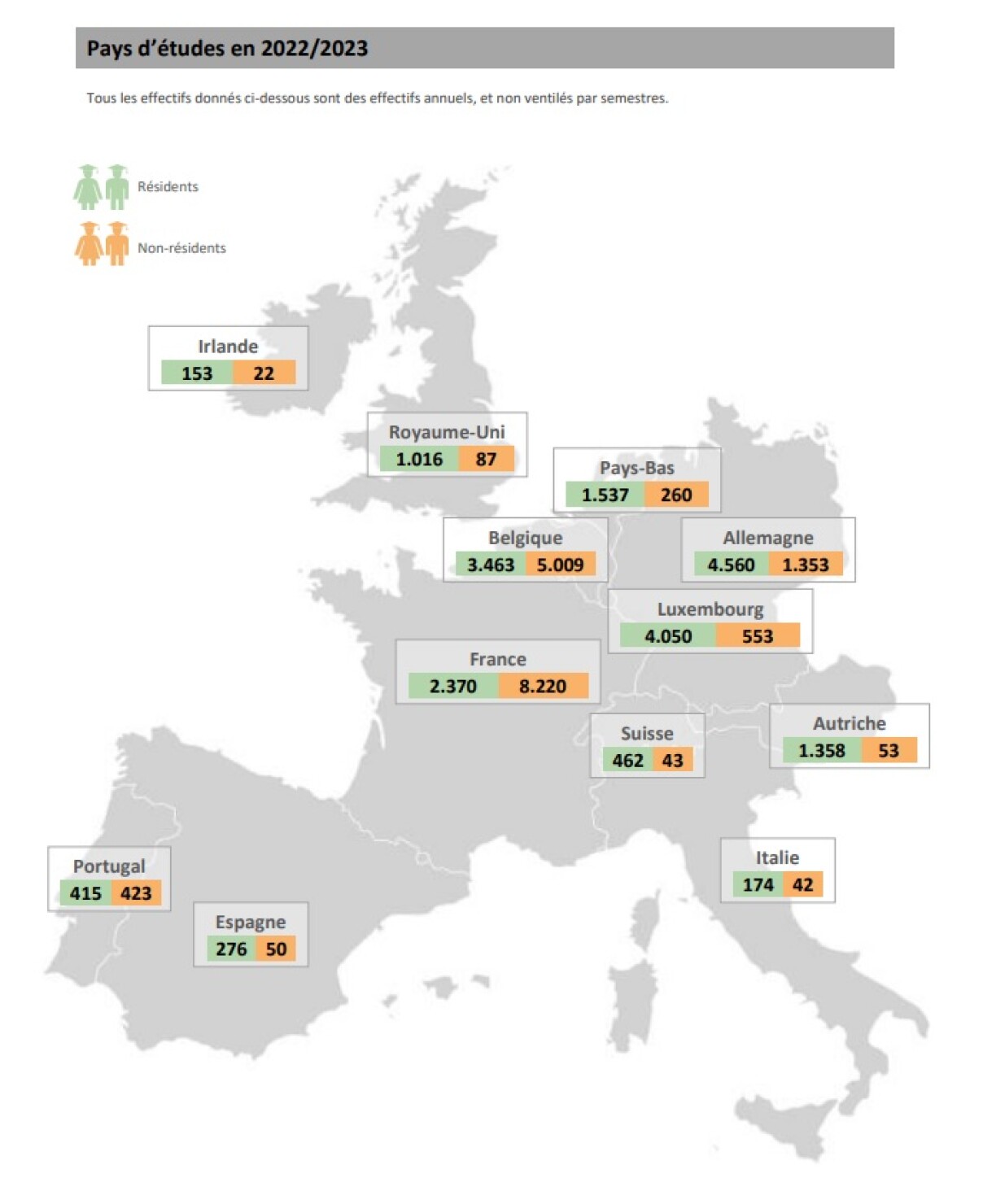

Another sign of the waning interest in French is reflected in the choices of higher education destinations for students from Luxembourg. According to the Ministry of Higher Education, 13% of these students chose France in 2013. Ten years later, only 6% of resident students (or at least those who received state aid) opted for France. In 2022/2023, Germany was the most popular destination, followed by Luxembourg and Belgium. However, when including non-resident students, France leads with 8,220 recipients of financial aid.

In summary, although it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from these partial data, there are indications—such as the need to revamp French language education—that French is no longer as favoured by Luxembourg’s youth as it once was. The true impact of these educational reforms will be clearer when students entering the 7th year (first year of secondary school) in September are assessed. This will be the first cohort to have experienced the new French teaching methods.