The expression ‘Disenchantment of the world’ was first used by German sociologist Max Weber in the early 20th century to describe a process in which the modern world rapidly characterised itself by rationalisation, secularisation, and the decline of traditional beliefs and magical thinking. Such disenchantment - the vanishing of the religious and the sacred from our world - was then borrowed from Weber by feminist scholar Silvia Federici.

Reinterpreted by her politically, the disenchantment I’d like to discuss lies in the emergence of a world in which we lose the capacity to recognise the existence of a logic other than that of capitalist development. This disenchantment corrupts our relations to land, resources and labour. Today it culminates in a housing crisis, corporate monopolies and wage slavery.

Students of architecture, in our master thesis research, my friend and colleague Christine and I asked ourselves: What does this disenchantment mean architecturally? How could we use our architecture to resist it?

We decided to start by looking into and learning from the most enchanted of all the architectural forms: the ruin.

(A little disclaimer before we proceed - In the previous ROUX issue, I wrote a short overview on the history of ruins where I explored how they had been exploited for centuries: from mining their materials and romanticising their aura to becoming a tool for modern economic and urban development. I kindly suggest you take a look at it before we go on.)

Scholars researching the phenomenon of ruin today agree about its power to transform our perception of time and space. The slow disintegration of abandoned buildings is anti-modern - it exposes what modernity seeks to conceal, revealing that its vision of continuous progress is nothing but an illusion.

Instead, the ruin phenomenon can help us understand the current system in which we live as a repetitive cycle of destruction. This discovery forces a reevaluation of capitalism’s true impact on society and the environment: architectures, communities, and ecologies ruined.

These transgressive qualities turn ruins into potential places of rebellion, alternative ways of living guided by the values of care and repair we would like to explore in our thesis. What if we reclaimed the modern ruins of our cities as a refuge for vagabonds and witches, as places of resistance against the disenchantment of the world under capitalist exploitation?

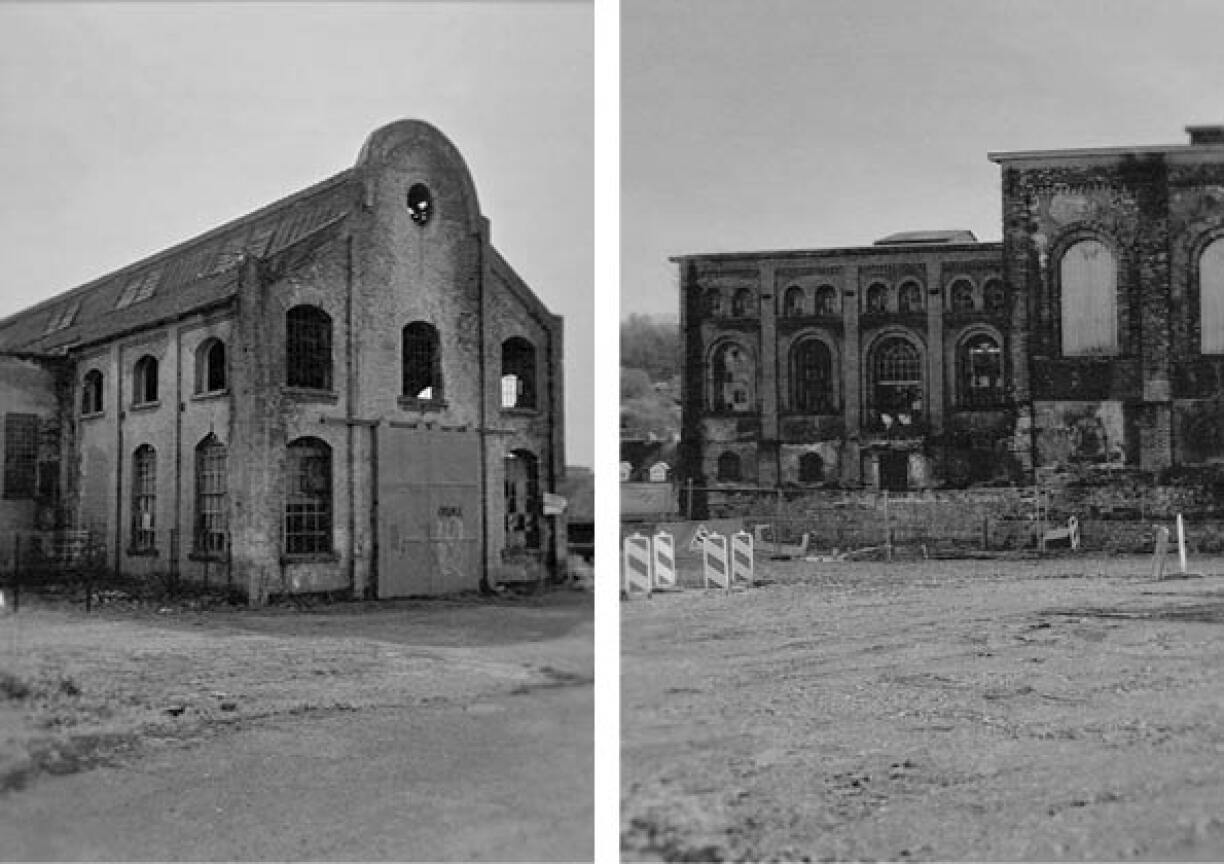

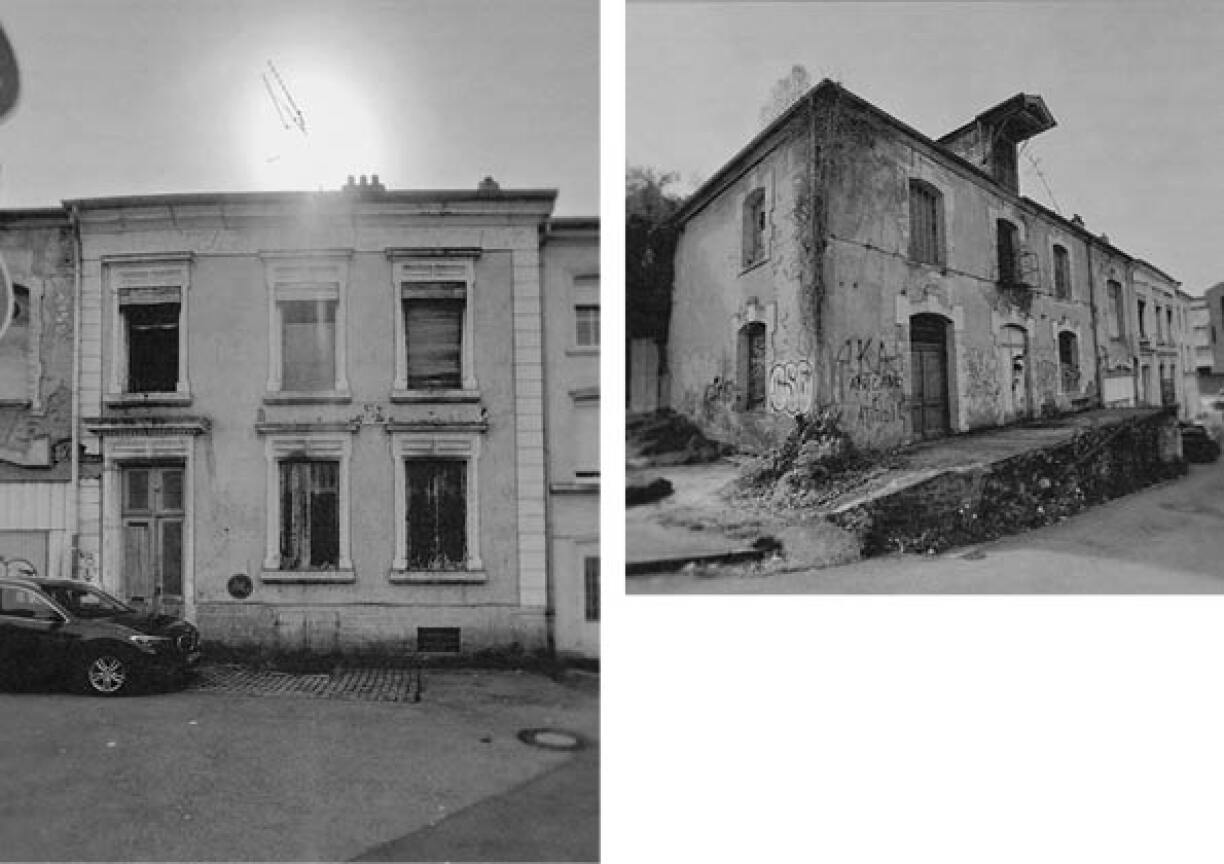

Take a closer look at the abandoned factory in your hometown: feel its crumbling walls and overgrown courtyards triggering our collective (albeit a little rusty) imagination; accept the ruins’ invitation to explore other ways of living in the broken world. In the context of a society increasingly alienated from its history, culture, and environment, ruins force us to confront the modern narratives that seek to erase the traces of the past.

They are a perfect base camp for all of those who wish to embrace the complexities and contradictions of our shared heritage.

Then, who are the witches and vagabonds of Luxembourg? For years young people, immigrants, and even Luxembourgish families have been exiled from their homes to Trier, Metz and border regions because of unaffordable rent. As a result, the inhabitants consist of a very homogenous middle-class that can afford a rent of 2000 euros a month.

Reclaiming ruins for affordable social housing would help bring these communities back home, and, while at it, preserve our architectural and cultural heritage. Thus, we would end up reclaiming not only physical space but also the power - arguably, magic power - to shape our cities.

The first step in reclaiming ruins is, first and foremost, to locate them. There are multiple ways through which we have been researching over the past 3 months: walking on site, consulting archives, talking to locals and tracing the evolution of the facade through years on Google Maps.

We’ve found many abandoned buildings in the vicinity of the Esch-sur-Alzette city centre. Some of them are too wrecked to live in, some are only beginning to deteriorate. All of them have lain abandoned for at least 7 years.

Upon analysing these buildings’ ownership, we’ve found that none of the abandoned buildings were owned by actual small owners, average citizens like us. It’s always either the commune, the state, big corporations, or real estate investment companies. Hence, the decaying buildings are often located in clusters, each of them having the same corporate owner. In our master thesis, we are going to investigate if it’s still possible to tear these ruins out of the speculation cycle and “re-enchant” them.

If yes - then how? Surely, we would not want to make anyone interested in these answers wait for too long. The public defence of our master thesis will take place in SPEKTRUM, Rumelange on the 26th of June. There, you can get acquainted with our research and the design proposal itself - everyone is welcome to join our presentation and discussion afterwards!

Looking forward to seeing you :)

Roux Magazine is made by students at the University of Luxembourg. We love their work, so we decided to team up with them and bring some of their articles to our audience as well. You can find all of their issues on Issuu.