On 8 October, Luxembourgers will be called to the polls for the legislative elections. However, only those with citizenship will be able to cast a ballot in this country where almost half of the population is foreign and more than 200,000 cross-border commuters come to work every day.

It will not have escaped the attention of these cross-border employees that unlike in their countries of origin, no major political party in Luxembourg seems to be classified as far right. Yet, in December 2022, a rare incident occurred in the Chamber of Deputies in Luxembourg. Minister of the Economy Franz Fayot used the expression “extreme right” to describe the position of a member of the conservative Alternative Democratic Reform Party (ADR), the most right-leaning party of the Grand Duchy’s political spectrum.

Was Minister Fayot correct in his assessment or was it just a phrase used for political gains in an election year?

Fernand Kartheiser, MP for the ADR, believes there is no far right party in Luxembourg and says that Minister Fayot “did not like the criticism and in fact tried to discredit the person who put forward the arguments rather than responding to them. So that was politics.”

The ADR was originally a social movement created in 1987 around pension reform. Today, it is the most ‘nationalist’ party represented in the Chamber of Deputies and is part of the European Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists Party, alongside Giorgia Meloni’s ‘Brothers of Italy’ and the Polish ‘Law and Justice’ party.

In June 2014 when the law favouring marriage and adoption for homosexual couples was up for vote in Luxembourg, the only party to oppose it was the ADR.

For historian Lucien Blau, author of the reference book ‘Histoire de l’extrême droite au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg au XXe siècle’ (‘History of the Extreme Right in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in the 20th Century’), the ideas associated with the extreme right have evolved over time without ever disappearing:

“Luxembourg’s good fortune is not that Luxembourgers are by nature more welcoming or more open ... The fortune of the Grand Duchy is that the Luxembourgish model continues working well, that is to say that there is no economic crisis like in France or Germany. There are poor people in Luxembourg, there are problems, but they are not as exacerbated as in the neighbouring countries ... Far-right ideas have more difficulty advancing in a favourable economic climate, but Luxembourgers are not immune to xenophobia.”

Christophe Froehling, a blogger and history student, advocates vigilance as he scrutinises the evolution of opinions on the internet and on social networks. “Since 2011", he observes, “we have noticed that new movements have been establishing themselves, notably the movement of Joe Thein, a former member of the ADR ... We can say that in recent years, populist movements have been establishing themselves in Luxembourg, even if, at the level of our country, this far-right ideology cannot always present itself as far right.”

As for the ADR, which is sometimes accused of flirting with far-right ideas and is allied with similar parties at a European level, it denies falling into this category.

MP Kartheiser describes the European Parliament as “a bit of a world of its own. All these families are very heterogeneous ... It is not necessarily a political concordance that cements these alliances, but a concordance of interests. In the European Parliament, I think that the most heterogeneous families are those of the liberals, with certain parties that I consider extremist. In our country, it is true that there are parties that are viewed very critically by Western Europe, for example the PIS, VOX in Spain, or the new government party in Italy. But, it has to be said that most of these parties are democratic parties and are widely elected in their countries.”

In this election year, the ADR will have to clarify its positions to avoid new altercations in the Chamber, which Fernand Kartheiser did in conversation with our colleagues from RTL 5minutes: “For us, foreigners are most welcome, there are no negative prejudices. The difference between the ADR and the other parties is that we are advocates of integration because we want people who come here to be able to integrate fully into our society, to participate fully in life, particularly cultural life.”

According to Blau, “the tone is soft. They are the champions of a veiled discourse, of the unspoken. And the audience they address knows very well how to decode the at times cryptic language of the ADR.”

When it comes to defining the extreme right, the historian, who admits that “the discourse has changed but the substance of the ideas has never varied”, says that it is “the negation of the values of 1789. Anti-liberal, against the principle of equality, cultures, and races. It is anti-parliamentarian, it refuses the philosophy of enlightenment, of the exercise of power by the people with its institutions. It is xenophobic, it always speaks of a national community ... A vision of a united people threatened from within by what is called the other. Yesterday the Jew, today the immigrant or the refugee. Those who have a different culture.”

According to Froehling, in recent years nationalist debates in the Grand Duchy have crystallised around language: “If we are told that the language is in danger of dying, this is a threat for our personality, our identity. That’s why people are always trying to play with this danger around a language that is in fact developing, that is not at all sick.”

Blau traces the origins of this ideology to the creation of the ‘Union nationale luxembourgeoise’ (‘National Luxembourgish Union’) in 1910, which was influenced by the theses of French essayists Maurice Barrès and Charles Maurras.

“Discourse always revolved around the fear of disappearance of the Luxembourgish nation, which would be submerged by waves of immigrants and that Luxembourg would then lose its language, its culture, its traditions. This discourse was repeated in the 1980s when the FELES [Federation ‘Our country, our language’] was founded. And it was said that the Luxembourgish language is under threat as immigration rose to unprecedented levels.”

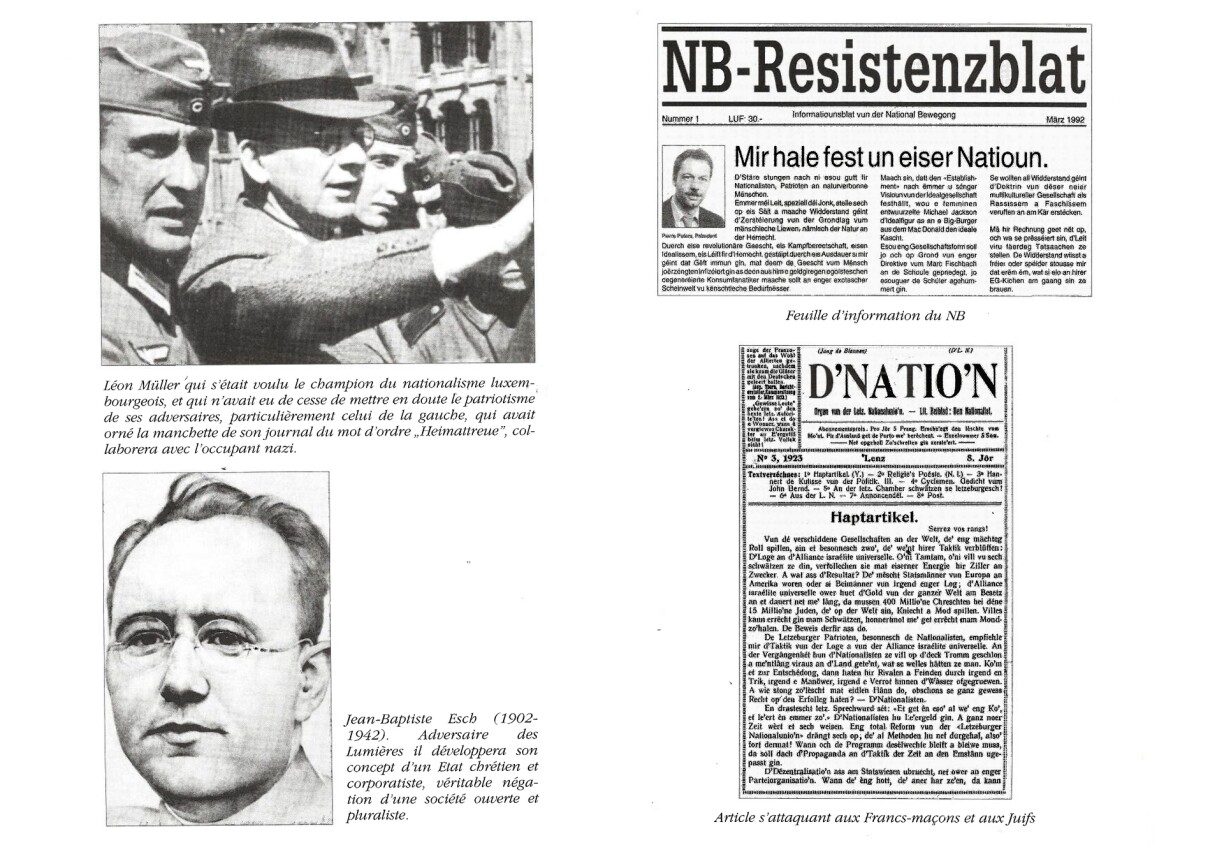

As everywhere in Europe, anti-Semitism, xenophobia, and nationalism were on the rise in the Grand Duchy in the 1930s through various movements and newspapers (the ‘Luxemburger Wort’ and the ‘Luxemburger Volksblatt’) and the champion of Luxembourgish nationalism, Léon Muller, even collaborated with the Nazi occupiers.

In the 1980s, the FELES already considered the Luxembourgish language under threat. The ‘Nationalbewegong’ (‘National Movement’) participated in two legislative elections, in 1989 and 1994. The scores obtained in 1994 (3.23% in the South, 2.03% in the East, 2.38% in the Centre, and 1.85% in the North) show the low support for the movement at the time. Later, the far-right activist Pierre Peters, co-founder of the ‘Nationalbewegong’, was convicted several times for inciting hatred.

In 2023, it is not possible to clearly state that the extreme right is politically represented in Luxembourg. For MP Kartheiser, who wants to make the ADR acceptable, “all these extremist tendencies are completely alien to our thinking. So, it is an argument that is simply used to try to discredit a political opponent.”

Blau does not share this perception: “I do not see why, in Luxembourg, we should have a different position than in other countries. In other words, the themes espoused by the ADR, the identity themes, this opposition to the Europe of Brussels, ... this theme of the decadence of values, of the threat of immigration, of refugees in Luxembourg, these are the themes of the European far right.”

Whether prevalent or underlying, this extremist thinking deserves vigilance for Froehling: “We always think that Luxembourg has certain defence mechanisms against far-right, populist ideologies. But, even a prosperous and calm country like Luxembourg has challenges to face [...] Because Luxembourg is a small country and we have a society that is based on a social network, Facebook, there is always the possibility to change opinions very quickly. That’s why there is a lot of potential to exploit opinions.”