The 19th century was a period of upheaval for Luxembourg, shifting from French rule to a Grand Duchy in 1815, enduring partition after the Belgian Revolution, and facing both a revolution in 1848 and a coup in 1856.

The turbulence peaked with the Luxembourg Crisis of 1867, when France and Prussia nearly went to war over the territory, leading to the Second Treaty of London, which secured Luxembourg’s independence and neutrality.

By 1868, stability was sorely needed – and Emmanuel Servais was the man to provide it.

Listen to this episode right here – and get to know more about other grand old men – or continue reading below.

Lambert Joseph Emmanuel Servais was born in French-occupied Mersch in 1811. A gifted student, he excelled at the Athénée of Luxembourg, finishing top of his class in his final two years.

As the Grand Duchy fell under Dutch rule, his ambitions turned northwards, leading him to Ghent in 1829 to study law. However, the Belgian Revolution of 1830 disrupted his studies, forcing him to relocate to Paris for a time before completing his doctorate in Liège in 1833.

Servais embraced the Belgian cause and reinforced his ties to the country by joining the bar in Arlon that same year, where he practised until 1839. Yet law was not his only pursuit – he co-founded Echo du Luxembourg in 1836, an Arlon-based journal opposing any partition of the Grand Duchy.

His campaign was ultimately unsuccessful. With Arlon now part of Belgium, he chose to return to the truncated Grand Duchy in 1840. Admitted to the bar in Luxembourg, he settled further with his marriage to Justine Boch in 1841 – the same year his political career began to take shape.

Recognising his abilities despite his past pro-Belgian stance, Dutch King William II appointed Servais to the traditional Assembly of Estates in 1841 as a representative for Mersch.

Over seven years in the Assembly, he gained popularity for his liberal views and willingness to challenge the government. Yet, like many European liberals of the time, he was not a fervent supporter of the 1848 revolutions. At the height of the unrest in Luxembourg that March, his house in Mersch was even defaced by protesters.

Despite this, Servais welcomed many of the proposed reforms, including the abolition of censorship, judicial independence, and the creation of a Constituent Assembly. Elected to that body, he played a key role in shaping Luxembourg’s new constitution, drawing heavily from Belgium’s model.

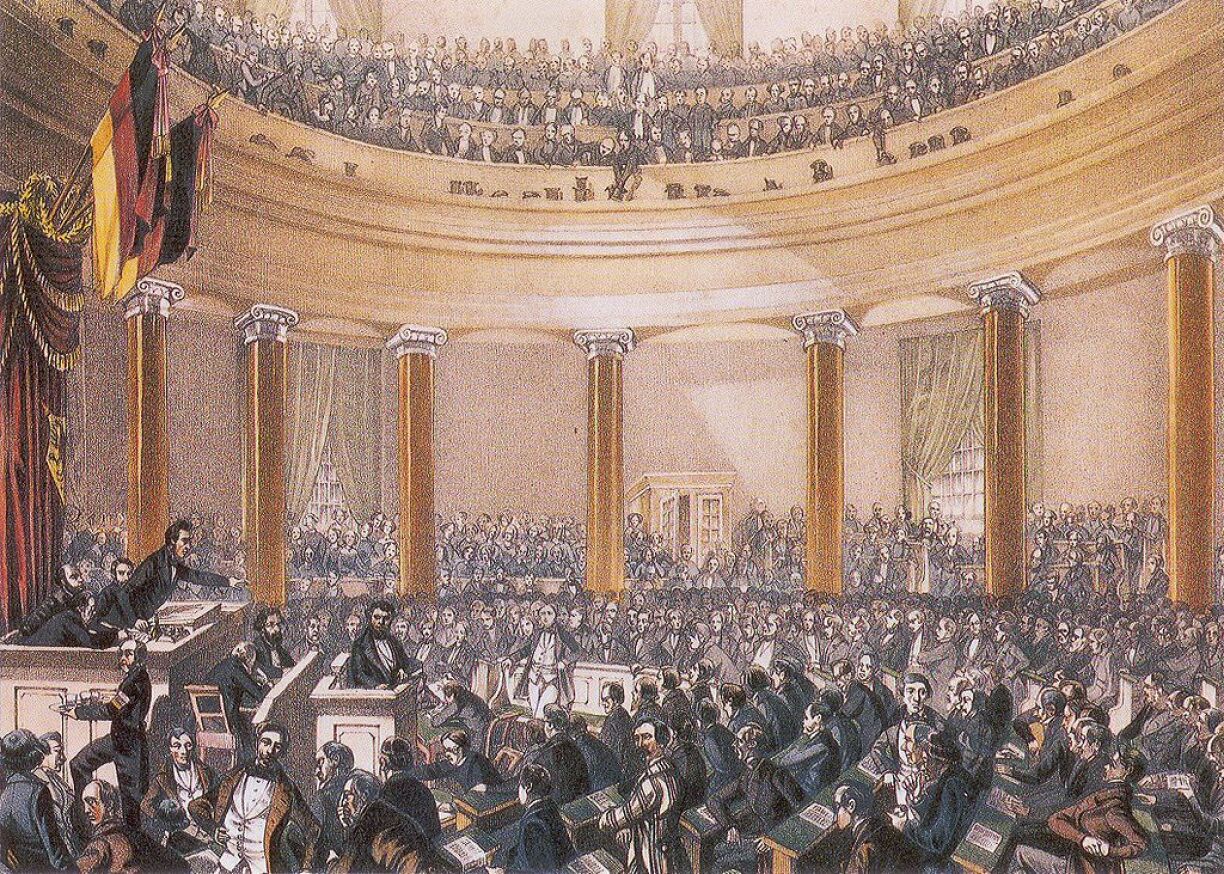

Servais’ growing influence was underscored by his nomination to the Frankfurt Parliament in 1848, where he and his colleagues sought to safeguard Luxembourg’s sovereignty within any future German state – a stance that put them at odds with more progressive liberals.

By the 1850s, however, his views had shifted. Finding the 1848 Constitution too liberal, he gained a reputation as something of a reactionary. In 1853, he became Director-General of Finances under Prime Minister Charles-Mathias Simons, a position he retained through the coup d’état of 1856, signalling his tacit support for the move.

After resigning in 1857, he spent the next decade in an advisory role on the newly established Council of State. His political stature remained undiminished, and in 1867 he was appointed plenipotentiary to the negotiations that led to the Second Treaty of London.

With the fall of Baron de Tornaco’s government later that year, Servais was poised to take centre stage in Luxembourg’s political landscape.

Emmanuel Servais took office in December 1867, tasked with implementing the Treaty of London. Chief among its provisions was the dismantling of the fortress of Luxembourg – an enormous project costing nearly two million francs and spanning until 1883.

He also oversaw the introduction of the 1868 Constitution, which reinstated ministerial responsibility, safeguarded press and association freedoms, and restored the Chamber of Deputies’ power over the annual budget.

The late 1860s and early 1870s marked the dawn of Luxembourg’s industrialisation, and Servais played a key role in expanding the country’s rail network and accelerating the growth of its iron and steel industries. His government also paved the way for financial modernisation, passing an 1873 law that led to the creation of Luxembourg’s national bank.

Religious affairs were another major challenge. Servais navigated tense negotiations over the establishment of a national diocese, culminating in the appointment of Nicolas Adames as Luxembourg’s first bishop.

His greatest test came during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Facing intense pressure from Bismarck, he successfully upheld Luxembourg’s neutrality by calling on the signatories of the 1867 Treaty to honour their commitments.

After seven demanding years in power, Servais resigned in late 1874, though his political career was far from over. He remained on the State Council until 1887 and served as Mayor of Luxembourg from 1875 until his death in 1890.

In many ways, Servais laid the foundation for modern Luxembourg. His leadership shaped the country’s political, economic, and industrial future, securing his legacy as a giant of Luxembourgish history.

Thank you for tuning in! Now what are you waiting for – download and listen, on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.