The year 1848, often referred to as the Springtime of the Peoples, holds a pivotal place in modern history. This year saw a wave of revolutions sweep across Europe, from France and Italy to the German states and the Habsburg Empire in Austria and Hungary. In Luxembourg, a notable outcome of this revolutionary wave was the establishment of a new Chamber of Deputies, which continues to exist to this day.

Listen to the episode right here in this podcast episode or continue reading down below.

The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg’s independence, conferred in 1815, was confirmed in 1839 after the tumults of the Belgian Revolution. It remained in a personal union with the King of the Netherlands, who was also Grand Duke of Luxembourg, but from 1840 to 1848 under William II Luxembourg set about creating its first modern administration.

In 1841, the popular William II – still commemorated today with a statue of him on horseback on Place Guillaume II – introduced the first ever constitution in Luxembourg, known as the Charter of the Estates. The constitution left sovereignty entirely in the hands of the Grand Duke, while the new Assembly of the Estates was virtually powerless and elected only by men over the age of 25 who paid 10 florins a year for the privilege, restricting the franchise to only around 3% of the population.

This left the (small) bourgeoisie, the peasants, the artisans and the nascent working classes entirely outside the administration of the new state, and there was no freedom of the press or of association.

In 1842, Luxembourg entered the Prussian-led Zollverein customs union, alleviating some of the worst economic problems that had plagued the Grand Duchy since its inception, but as industrialisation had not yet set in, the economy remained primarily agricultural, and the Zollverein was not popular with the people.

Overpopulation and bad harvests led to occasional famines in the Luxembourgish countryside, such as in 1839–40 and 1842–43. Between 1841 and 1846, the great potato blight which resulted in a famine in Ireland caused the price of potatoes to triple in Luxembourg. And the Grand Duchy would also be affected by the European-wide economic crisis of 1845–47.

A general downturn put many of the country’s artisans and workers out of work, while punitive legislation such as an 1845 ban on using straw roofs for houses hit the poor particularly hard. Beset by economic problems and receiving no help from an elitist government, the Luxembourgish population was ready to revolt.

Across the continent, similar social, economic and political problems caused discontent to rise among the European population. The first revolutionary event of the year actually took place in Sicily, but the real trigger was the February Revolution in Paris which overthrew King Louis-Philippe.

As news of the French success spread, barricades then went up in most of the cities of Central Europe, while uprisings in Italy and Hungary led to the outbreak of nationalist wars against the Austrian Habsburgs. In Germany, the Frankfurt Parliament was set up with the intention of creating a unified German state, while dukes, princes and kings granted their citizens constitutions out of fear of socialist revolutions.

One such panicky monarch was Grand Duke William II.

When news of the February Revolution reached Luxembourg, it served as the trigger for popular unrest. Petitions, an ancient form of protest which had been banned under the Grand Duchy, soon began to flood the government in Luxembourg from across the country.

Then, in Ettelbruck, a protest movement broke out in early March, during which cries of ‘Vive la Republique’ and ‘Merde pour les Prussiens’ were heard, while the Marseillaise was apparently also sung.

The house of the mayor of Luxembourg, Fernand Pescatore, was attacked on March 16th, and various other disturbances occurred in towns across the Grand Duchy, including in Wiltz, Esch-sur-Sûre, Mersch and Echternach. Fearing the worst, and perhaps influenced by his father’s counter-productive reaction to the Belgian Revolution, Grand Duke William II conceded to the protesters on March 20th, and a new Constituent Assembly was charged with creating a better constitution for the Grand Duchy.

Meanwhile, liberty of the press was granted, with the Luxembourger Wort being formed on March 23rd, 1848.

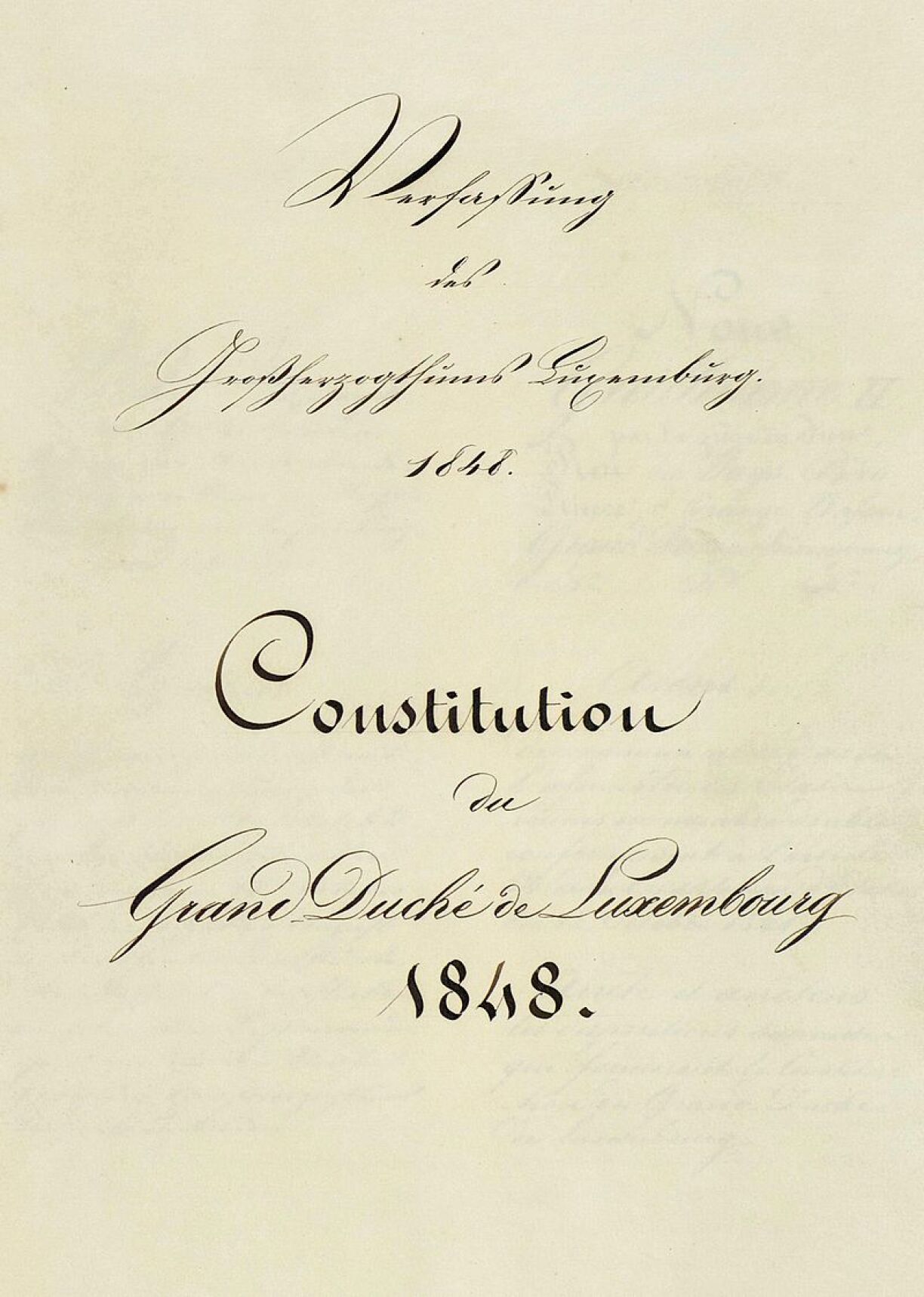

The Constituent Assembly convened in Ettelbruck on 25 April. By the end of June, they had drafted a new Constitution, which the Grand Duke approved in July. This new Constitution came into effect on 1 August.

So, was this a revolution?

In the social sense, perhaps not, as government troops managed to suppress the protests without any casualties. However, politically, a revolution had indeed occurred. Luxembourg effectively transformed into a constitutional monarchy overnight.

The new constitution, modelled on the Belgian Constitution of 1830, set far greater limits on the power of the Grand Duke, created a new unicameral Chamber of Deputies with legislative sovereignty and the power to vote on budgets, and set up an independent judiciary. This was a strongly liberal and progressive constitution for the time, even if the franchise was barely extended, with only 5% of the electorate eligible to vote.

The foundation of the Luxembourgish government had thus been set. But the death of William II led to a renewed constitutional crisis in the Grand Duchy, as his successor William III took the new Chamber of Deputies head on.

Thank you for tuning in! Now what are you waiting for – download and listen, on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.