The charging infrastructure in the EU will be greatly expanded and harmonised. On Tuesday night, representatives of the European Parliament and of the member states reached a broad agreement. Among other things, by 2026, it should be possible to charge an electric car every 60 kilometres on main transport axes. In addition, payment modalities are to be made more uniform.

The first question that many people rightly ask is how far you can currently drive autonomously with an electric car. How far have we come, to what extent is autonomy still a concern, and to what extent could it be improved further?

Prof Dr Martin Doppelbauer, professor for hybrid-electric vehicles at KIT, the Institute of Technology in Karlsruhe, says: “The autonomy of electric cars is absolutely practical today and no longer poses any restrictions in everyday life. Typical city cars with capacities of 50-60 kilowatt hours can reach a distance of 250 kilometres even in winter. Family cars with capacities of around 70-90 kilowatt-hours may travel 350 kilometres in winter and much further in summer. Battery-powered vehicles are the only mass-market alternatives to the internal combustion engine. There are almost ten million of these vehicles on the road worldwide.”

Furthermore, Dr Doppelbauer emphasises that synthetically produced e-fuels will probably remain far too expensive in the long run due to the large production effort involved. In this case, they could not be made available for the operation of many millions of vehicles: “The enormous effort required to produce these fuels also accounts for the large CO2 emissions, which is why they always have a significantly worse environmental balance than electric cars - there is simply no question of zero emissions in the overall balance. Also, there are local emissions in cities that will not be decreased by e-fuels.”

It would also make far more sense to use these e-fuels in situations when there are no other options for decarbonization, such as ships or aircraft.

Another problem is the price of vehicles, which is still too high in some cases, or the limited supply of low-cost vehicles. Prof Dr Dirk Uwe Sauer, Professor for Electro-Chemical Energy Conversion and Storage Systems Technology at the University of Applied Sciences in Aachen (RWTH): “There are currently few compact and mid-range vehicles with long ranges that are priced similarly to conventional cars. The question is, however, how many vehicles in this class are driven over long distances. Greater flexibility, for example, could be achieved with offers that include renting cars with a long range in addition to buying the car, that could be quite attractive.”

Another critical aspect of electric vehicles is the charging time of the batteries. According to Prof Dr Doppelbauer, the charging period with a Hypercharger is currently 20 to 30 minutes, which is “short enough to cover greater distances without issue.”

Prof Dr Dirk Uwe Sauer adds: “The 350 kW technology can be applied to high-end vehicles that can travel over 400 kilometres on a single charge. This recharges the energy for around 100 kilometres of autonomy in approximately three minutes. But because the battery cannot be fully charged at this speed, this would mean having to recharge for ten minutes about every 300 kilometres. If cars become more efficient, this time might be decreased to 2 minutes for a 100-kilometer trip with the same performance. In my view, this would not be a great restriction of mobility compared to conventional combustion engines, especially since most drivers like to use breaks to relax and catch up on their digital messages.”

The vast majority of people who drive electric cars rapidly adapt to the rhythm, and only a few find it irritating or disagreeable.

The maximum outputs of cars with small batteries, which are built for traversing shorter distances, will be lower since the batteries cannot absorb the high outputs of charging stations. In these cases, according to Dr Dirk Uwe Sauer, charging time will increase to 5-6 minutes per 100-kilometre range. Car and battery designers are trying to enhance battery performance, but this of course means that they will become more expensive again. Compromises between battery prices and charging speed will have to be made.

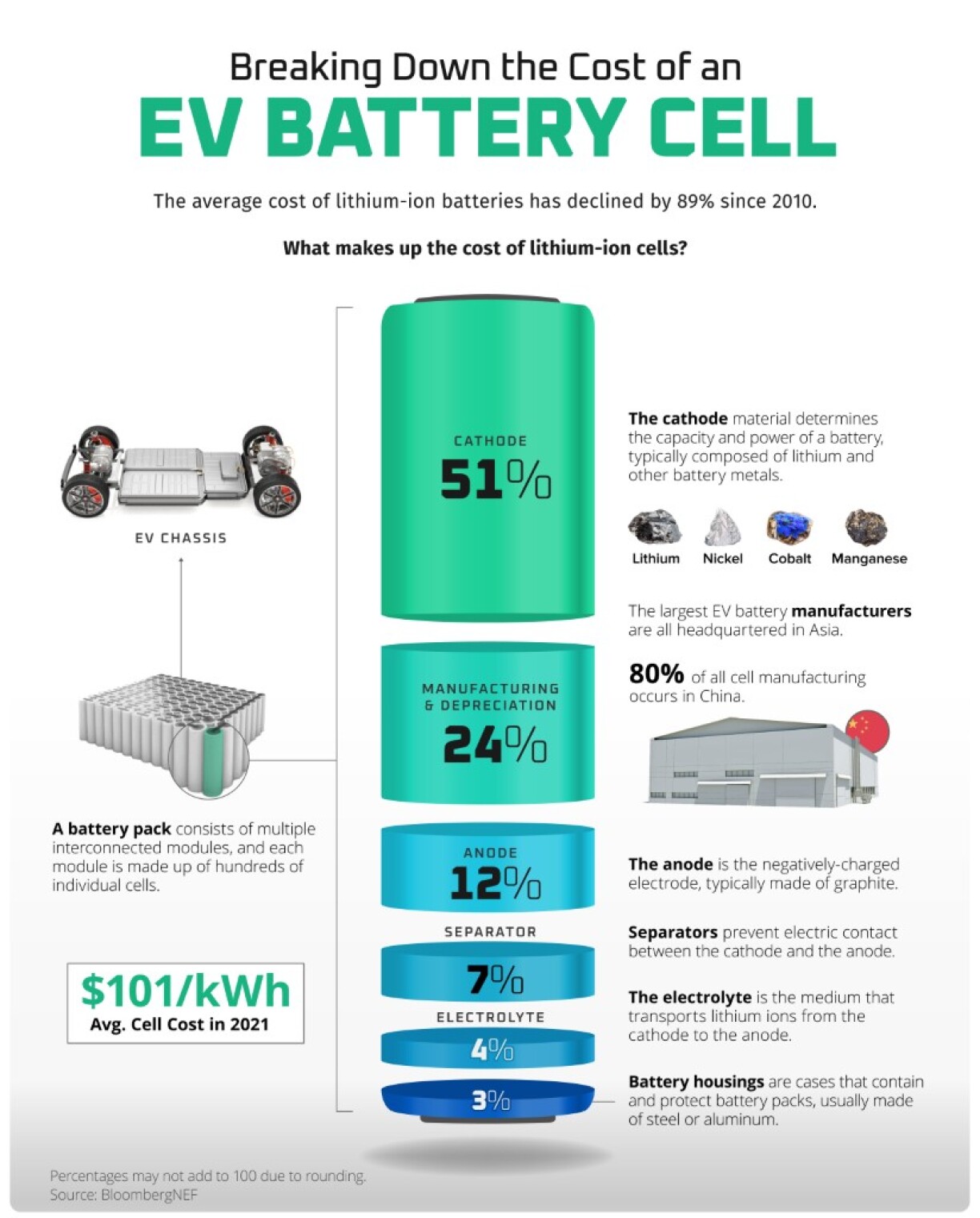

The issue of raw materials is crucial in the discussion of electromobility. Is there enough environmentally friendly capacity to extract lithium or other rare substances, or could the danger of dependency arise again?

Prof Dr Doppelbauer: “Battery technology is still being developed. Raw materials such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, or manganese may no longer be needed in the future. Many cars already have lithium iron phosphate batteries that do not contain these raw materials. Rare earths are not used in batteries, by the way. What appears certain is that we will not be able to avoid using lithium in high-performance batteries in the long run, despite the fact that the first sodium-based batteries are just entering production, albeit with only around half the energy density.”

Fortunately, there are large quantities of lithium all over the world, even in Germany, and the raw material can now be extracted in an environmentally friendly way. Martin Doppelbauer stresses that batteries are easy to recycle, and a large part of the materials used can be recovered.

Prof Dr Dirk Uwe Sauer: “Lithium extraction capacity will become scarce in the next years. These capacities are being expanded; nevertheless, nations with big lithium reserves, such as Argentina or Bolivia, are not currently contributing significant capacities. The price of lithium is currently so high that even relatively tiny quantities may be used economically. Therefore, I expect that there will only be a brief market shortage.”

In addition, sodium-ion battery technology, for example, will provide some relief in the raw materials market for lithium-ion batteries in various segments. The lithium scarcity, however, will be temporary, and the problem will not be solved by switching to other technologies such as fuel cells, hydrogen, or e-fuels because production capacities here are extremely limited and demand cannot be fulfilled, according to Dirk Uwe Sauer.

Cobalt will also be used less and less in car batteries. Lithium iron phosphate and sodium ion batteries are alternatives. These can be used primarily in cheaper cars and for stationary use, thus providing further relief to the raw materials market.