In 1984, almost 80% of the trees in Luxembourg’s forests were healthy. But by 2023, that number had plummeted to just 15%!

That’s wild, isn’t it? 73% of our trees are showing signs of damage or stress; 12% are severely damaged or already dead.

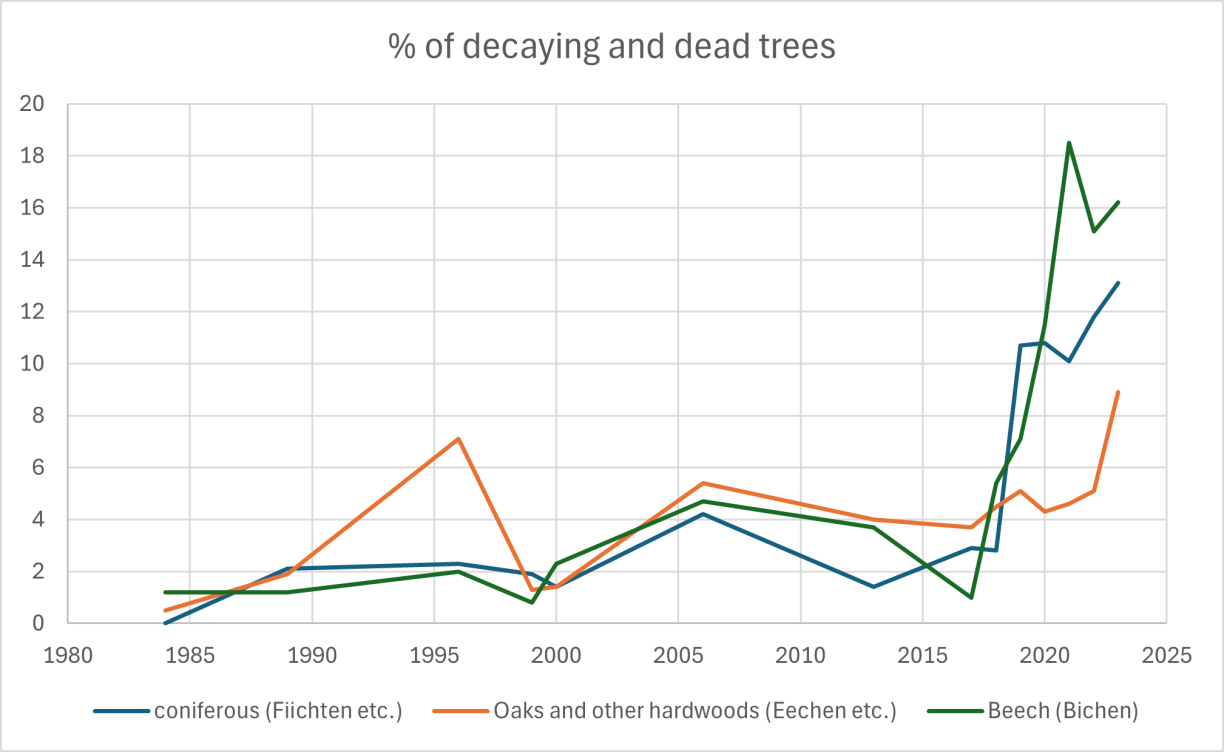

The past five years are particularly striking. From 2019 onwards, forest health has declined drastically.

To assess forest health, a sample from the European network of observation plots has been collected annually in Luxembourg since 1984. This is a systematic network of 51 observation plots laid out in a 4 x 4 km grid, in both public and private forests. For the 2023 condition report, a total of 1,176 trees on these plots were assessed by specialists. The following aspects were recorded:

Each examined tree is assigned to one of five condition categories (0 = undamaged trees; 1 = slightly stressed or damaged trees; 2 = moderately stressed or damaged trees; 3 = severely stressed or damaged trees; 4 = dead trees). The data are used in international comparison studies, including those carried out through ICP Forests, an EU programme for monitoring forest health. (Source: ANF)

For many people, forests are a place of calm and recreation. It also helps regulate our climate, provides a home to a wide range of animals and plants, and is a valuable resource for sustainable building material.

But will this still be the case in the future?

In our new Ziel mir keng! episode, with support from Martine Neuberg, head of the ‘Forests’ department at the Nature and Forest Agency, we took a closer look at the current state of Luxembourg’s forests and what lies ahead for them.

A few thousand years ago, when human populations were small, our part of the world was almost completely covered in forest.

Today in Luxembourg, forest cover is only about 36%.

That’s slightly more than in our neighbouring countries, France and Germany, quite a bit more than in Belgium, but still below the European average of 41 %.

Luxembourg has around 92,150 hectares of forest. According to the second forest inventory, about 68% of this area consists of deciduous trees and 32% of conifers. There are only a few mixed forests: one exception is the combination of pine and beech.

In Luxembourg, 54% of the forest area is privately owned; the rest is public property.

Over the years, a large part of the forests has been lost due to human activity, mainly because we needed space for towns, villages and agriculture.Much of the forest that still exists is now stressed, damaged or even dead.

Beeches are currently the most severely affected. For the first time, none of the beech trees examined in 2023 could be classified as undamaged. The situation is similar for oaks and other deciduous trees, although 10% are still undamaged. The condition of conifers appears to be stabilising.

But just how bad is that? First up, let’s take a look at why forests are so important in the first place.

The forest has three main functions.

For example, forests are important in the fight against climate change. Through photosynthesis, trees pull CO₂ from the atmosphere and, with the help of water, convert it into oxygen and sugar.

So, this process captures CO₂ from the air, storing the carbon in the wood. The fewer healthy trees there are, the less CO₂ is captured.

By the way: one hectare of forest in Luxembourg can absorb about ten tonnes of CO₂ per year. In comparison, at the moment, the average CO₂ emissions in Luxembourg are around 13 tonnes per person, per year!

And forests also help to provide local cooling. Because forests hold a lot of moisture, evaporation is constantly taking place, which draws heat out of the surrounding environment. You’ve surely noticed how wonderfully cool it is inside a forest during the summer.

For example, the forest also helps to filter our drinking water and the air we breathe.

Depending on the type of forest, a single hectare can generate between 80,000 and 160,000 cubic metres of new groundwater each year and filter up to 50 tonnes of soot and dust from the air.

The forest ecosystem, meanwhile, is home to a whole host of creatures that are specifically adapted to this environment and can only live there. The forest is also important for biodiversity.

So, if our forests continue to decline, we’re going to face problems on several different fronts: we’re losing building material, economic heritage, a space for recreation, and a vital ecosystem in the fight against climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

But what are the reasons the forests are dying in the first place?

These days, acid rain is basically a non-issue. That was very different back in the 80s. But thanks to a whole range of measures, such as installing catalytic converters in cars, we’ve managed to get this problem relatively under control. A great example of how politicians took scientific warnings on board and actually made things better!

The main reason now is climate change. Climate change, for example, is causing more frequent droughts, which weaken or kill trees. Due to the lack of water, more trees have died in the forests in recent years, and particularly beech trees growing on heavy clay soils have suffered extensive damage.

It’s true, there have always been droughts. But because of climate change, we’re observing in Luxembourg and many other places that these kinds of extreme weather events are simply happening more often, statistically speaking.

What’s more, warmer winters also mean pests like the bark beetle are more likely to survive. In recent years, it’s caused massive damage, particularly to spruce trees.

These are natural enemies that have always existed. Either the trees cope with them on their own, for example by producing resin to get rid of the beetle, or proper forest management and maintenance can help limit the damage.

Recently, however, several effects have coincided: if it’s too dry, the tree can’t produce enough resin and can no longer defend itself properly. What’s problematic when it comes to the bark beetle is that our forests have a relatively high number of spruce trees. In Luxembourg, they’re one of the main tree species, after beeches and oaks.

After the Second World War, a lot of spruce trees were planted, often in monocultures, because they grow quickly and are really useful for the timber industry.

But the condition of the soil plays an important role too. There’s evidence that there are too many nitrates in the soil, caused by factors like car and industrial emissions as well as agricultural fertilisers, which leads to over-fertilisation.

This makes trees grow too quickly initially, leading to a nutrient imbalance that makes them more susceptible to pests in the long run.

In addition, natural processes also play a role, such as ageing. The trees and our forests are relatively old today.

So, how can we restore our forests and make them future-proof?

Scientists, foresters, woodland owners, conservationists, hunters, public authorities and others are all working to shape the forest of the future. They rely partly on scientific evidence.

This raises an important question: what kind of forest do we want? How much of it should be commercial woodland, and how much should be left wild?

The forest of the future definitely needs to help protect the climate and be more resilient. And so it needs to be adapted to the climate of the future.

One major challenge, though, is that it’s not clear exactly how our climate is going to change. Which trees will be best suited, bearing in mind that trees can live for several hundred years?* It’s almost impossible to make reliable forecasts that far ahead.

That’s why the consensus is not to rely on just one or a few tree species, but to aim for a certain amount of diversity. If we plant different types of trees, hopefully there will always be a few that survive.

The plan also involves reducing stress on our forests. In practice, that means protecting the soil, managing wildlife populations – because the animals often nibble on young trees – and, at the same time, not interfering too much with the forest. As much as needed, but as little as possible.

To achieve this, compromises are necessary and we need to remain flexible. For example, if we want to make the forest more resilient, interventions are necessary. These interventions can also make use of opportunities that arise from damage. Damaged trees can be removed and replaced with a greater variety of species that are better suited to the site.

*In our ‘Ziel mir keng!”'video, we mistakenly say that trees live “up to 200 years”. This is true for most trees planted for forestry use. However, trees can naturally grow older than this. Luxembourg’s oldest tree is estimated to be around 500 years old. It is an oak tree located in Altrier.

Our forests are in poor condition. This is not good, and one thing is certain: the forest of the future will be different from the forest of today.

There’s still something we can do, so that, hopefully, at some point, the forest can recover. That’s why it’s vital we recognise just how precious this habitat is – as a space for recreation, a source of resources, a place of sanctuary, for our climate, for biodiversity, for clean air and drinking water, and so much more.

Ziel mir keng! is broadcast on Sunday evenings after the programme Wëssensmagazin Pisa on RTL Tëlee and is a collaboration between RTL and the Luxembourg National Research Fund. You can also watch the episodes on RTL Play.

Authors: Michèle Weber, Jean-Paul Bertemes, (FNR)

Presentation: Michèle Weber, Jean-Paul Bertemes (FNR)

Consultation and Fact checking: Martine Neuberg (ANF)

Video and illustrations: SKIN

Translation: Nadia Taouil ( www.t9n.lu )