Men living in the poorest neighbourhoods in England live, on average, 9.7 years less (Office for National Statistics, 2022) than men in the wealthiest neighbourhoods. And in the EU, people without a secondary education diploma live four years less than those with a university degree.

Poverty is a tough reality for those affected and refers to a situation that is financially and socially unstable, and sometimes even life-threatening.

Scientific research is helping us better understand and measure this phenomenon, among other things to provide data for evidence-based action.

Studies show poverty negatively impacts the education and health of people affected, and escaping poverty is particularly difficult for those born into it.

Poverty researcher Olivier de Schutter describes it this way: “Poverty is a life sentence for something the child did not do.” (Olivier De Schutter, 2024)

Let’s take a look at some studies on this topic, and you’ll see that, fortunately, there is also more positive news!

For this episode, we received advice from Philippe Van Kerm (University of Luxembourg), Eric Marlier (LISER), Anne-Catherine Guio (LISER), and Guillaume Osier (STATEC), who also checked the facts.

When people think of poverty, the first thing that comes to mind is a lack of money. The World Bank defines someone as extremely poor if they earn less than $2.15 a day. In poor countries, this is the absolute minimum needed for survival (The World Bank, 2022). However, this indicator isn’t suitable for wealthy countries.

For these countries, we use “relative indicators”, which compare individuals against the national standard of living. In the EU, the at-risk-of-poverty rate is commonly used for this purpose. This indicator is triggered when a household’s disposable income per person is less than 60% of the median income.

Yes, that’s a lot of technical terms.

In Luxembourg, the at-risk-of-poverty threshold in 2023 was €2,382 per month for a single adult. If several people live in a household, the calculation becomes more complex. This means that in Luxembourg, around one in five people – or just over 120,000 individuals – are at risk of poverty.

By the way, around one in five people in Luxembourg also report having difficulty making ends meet by the end of the month. This is what we call a subjective indicator of poverty. But – and this is very important – poverty is not just a lack of money, but also leads to social exclusion. Poverty limits people’s ability to participate in social life.

To capture this, we use “deprivation indicators”. These indicators define specific items and activities a person needs in order to engage fully in society. For example, having access to the Internet or a car, being able to go on holiday once a year, affording new clothes, or meeting with friends or family at least once a month for a meal.

If someone cannot afford five out of the thirteen items on this list, they are considered materially and socially deprived, according to this indicator. In Luxembourg, this applies to 5.7% of the population.

First conclusion: Poverty has not only financial but also social dimensions. And in Luxembourg, more people are affected than you might expect for such a wealthy country.

Let’s now explore the impact poverty has on the lives of those affected. Growing up poor as a child increases the likelihood of being poor as an adult as well. The book The Escape from Poverty, whose authors include two researchers from Luxembourg, explains this quite well (De Schutter et al., 2023).

An international study shows that in France, for example, it takes an average of five generations for descendants of a very poor family to have a fair chance of achieving a middle-class income. In Denmark, it takes only two generations, while in Columbia, it takes as many as eleven (OCDE, 2018).

This doesn’t mean that individual poor people can’t suddenly become rich, but it does show how opportunities are not equally distributed.

So it is not true that wealth is purely the result of individual merit.

Second conclusion: People living in poverty face persistent disadvantages.

This marginalisation is reflected in several areas.

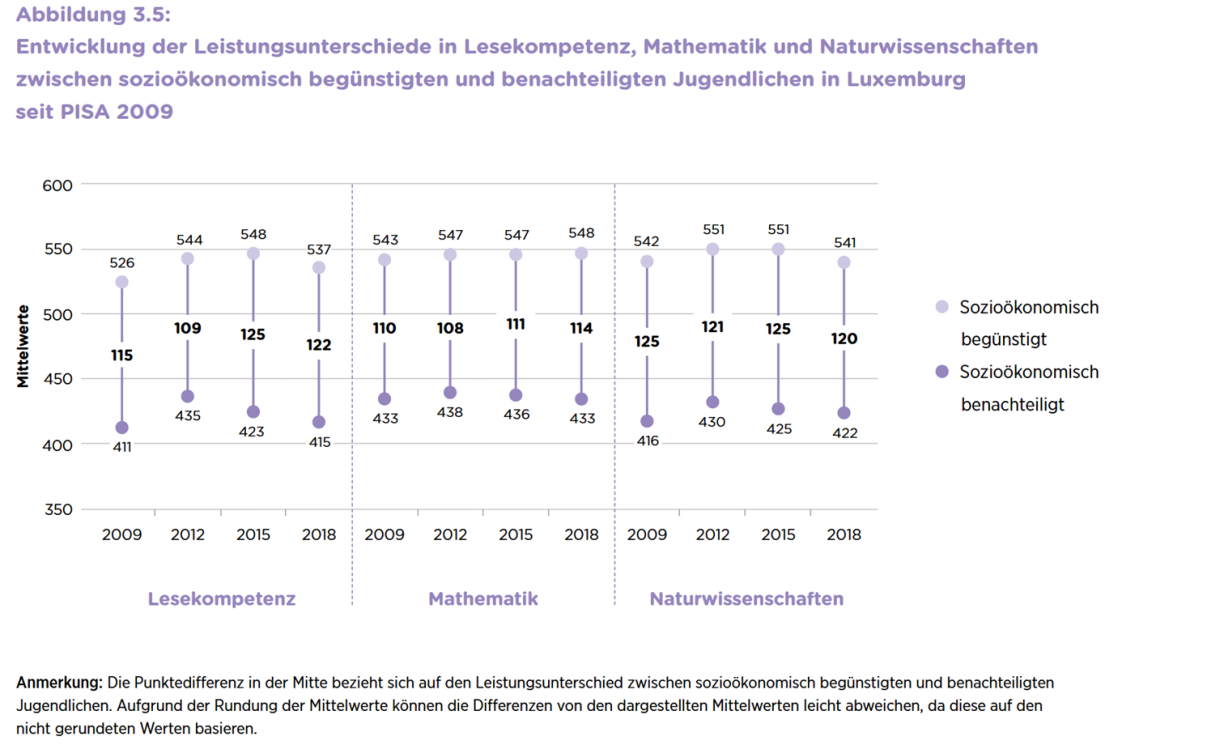

For example, children from socio-economically disadvantaged families tend to perform worse academically. In Luxembourg, the gap between students from weaker socio-economic backgrounds and their more advantaged peers is particularly pronounced (OECD, 2018; OECD, 2016; OECD 2013).

In the PISA study, Luxembourg students from the lowest socio-economic quartile were approximately three school years behind those in the highest quartile in reading proficiency.

They also lagged in mathematics and science, and were more likely to repeat a school year.

Of course, this is just a correlation. There are many reasons for this, but they are related to their disadvantaged background.

For example, disadvantaged families have less money to spend on adequate learning materials or private tutoring for their children. In Luxembourg specifically, another significant factor is one’s native language and migration background.

It’s also evident that individuals from low socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to suffer from mental health issues and chronic illnesses. As already mentioned, they also tend to have shorter life expectancy (OECD, 2023; WHO, 2014; OECD, 2018; Guralnik et al., 2006).

This is partly due to the stress caused by poverty, i.e. not knowing how to make ends meet. Such stress negatively affects both mental and physical health. In addition, stress often leads to unhealthy behaviours, such as alcohol consumption and smoking. People from poorer backgrounds also tend to have an unhealthy diet because they have less money to buy high-quality food products and less time to prepare fresh meals (Pampel et al., 2010).

Third conclusion: Poverty is closely linked to negative impacts on education, health and life expectancy.

Options include, of course, social transfers and financial support for those in poverty. What is interesting in this context, however, is that a whole range of instruments already exist, but they often fail to reach the people they are meant to help.

Researchers from Luxembourg, for example, have shown that 45% of those eligible for the cost-of-living allowance do not claim it. This figure rises to 80% for the rent allowance (Franziskus and Guio, 2024). Researchers are currently investigating why this is the case and are offering suggestions to improve the situation.

Another option is to provide people in poverty, including children, with access to quality education or training opportunities to empower them to create a better future for themselves.

There are numerous other potential pathways, and science can provide data, facts and methodologies, but it is ultimately up to politicians and society to decide the way forward.

Alright, that was a somewhat more challenging topic to discuss. But to wrap things up on a more positive note: globally, the number of people living in extreme poverty fell from 2 billion in 1990 to 692 million in 2024.

That’s why it’s worth keeping at it.

Ziel mir keng! is broadcast on Sunday evenings after the programme Wëssensmagazin Pisa on RTL Tëlee and is a collaboration between RTL and the Luxembourg National Research Fund. You can also watch the episodes on RTL Play.

Author: Jean-Paul Bertemes (FNR)

Co-author: Lucie Zeches (FNR)

Fact checking and advice: Philippe Van Kerma (University of Luxembourg/LISER), Guillaume Osier (STATEC), Eric Marlier (LISER), Anne-Catherine Guio (LISER), Daniel Saraga

Translation: Nadia Taouil (www.t9n.lu)