Biologically speaking, there are also intersex people – individuals with sexual characteristics that do not fit the binary notions of male or female. Some have, for example, both testicles and ovaries. Others have XX chromosomes but a penis. Still others have XY chromosomes but high levels of oestrogen. Some even have XXY chromosomes...

So are there really only two biological sexes? Or is it more like three? Or is there a whole spectrum? In this episode of Ziel mir keng! we will break down how biological sex develops, what intersexuality is, and how many sexes there really are!

When we talk about gender, several dimensions come into play, including:

In this article, we’ll focus on biological sex.

When we hear ‘biological sex’, we immediately think: man equals penis and woman equals vulva. But it’s not that simple. Biological sex is defined at several levels:

For the vast majority of people, all these characteristics align clearly as either male or female – but not always, which is what makes this issue more complex than it seems.

Let’s start with reproduction. There are only two types of reproductive cells: sperm and egg cells. This creates exactly two biological roles in reproduction: one male and one female. But we wouldn’t say to a man who cannot produce sperm that he is not a man. Or to a woman without egg cells that she is not a woman, would we?

Now, what about chromosomes? Our genes are packaged into a few chromosomes, with two different sex chromosomes: X and Y. In this case, the matter is much simpler: Women have two X sex chromosomes, while men have one X and one Y. That’s it, right? Not quite – there are also people with XXY chromosomes. Or with only one X chromosome. Or with a mixture of XX and XY chromosomes...

Okay, but surely reproductive organs give us clearer answers, right? Men have a penis and testicles, women have a vulva, ovaries and breasts. Yes, but not necessarily in the case of intersex people...

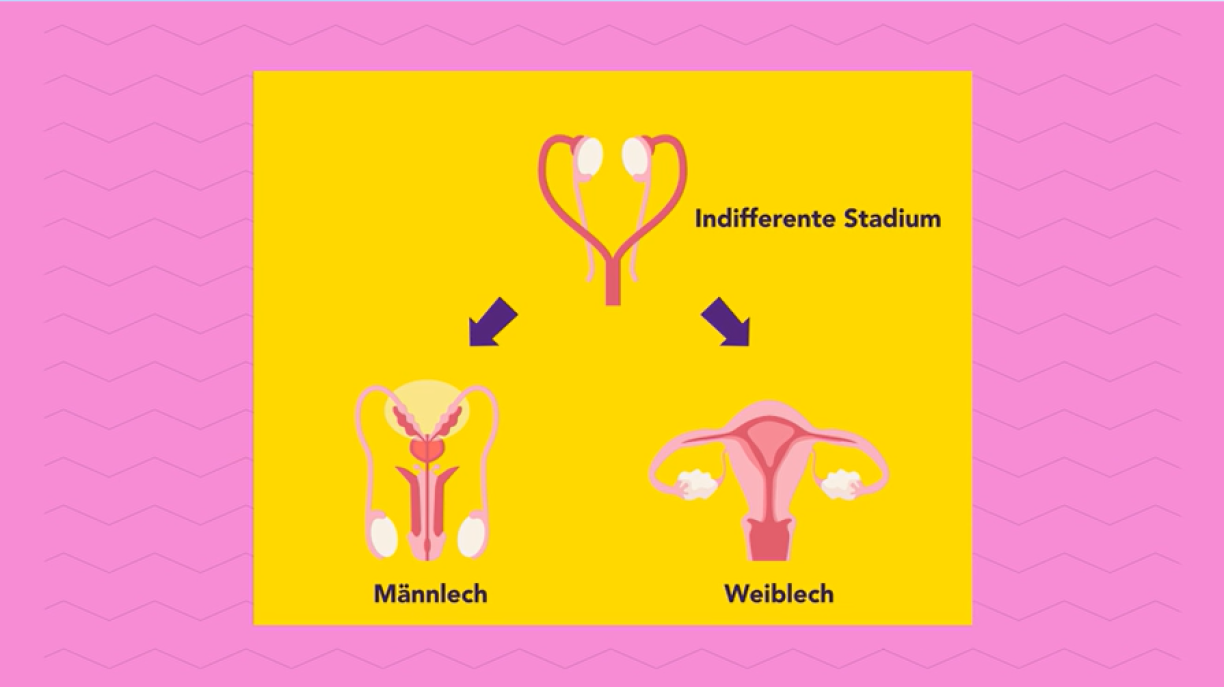

Let’s take a look at how sex develops in human embryos. Until week 6, embryos have neither male nor female traits. The internal sex glands and the external organs exist in an undifferentiated state.

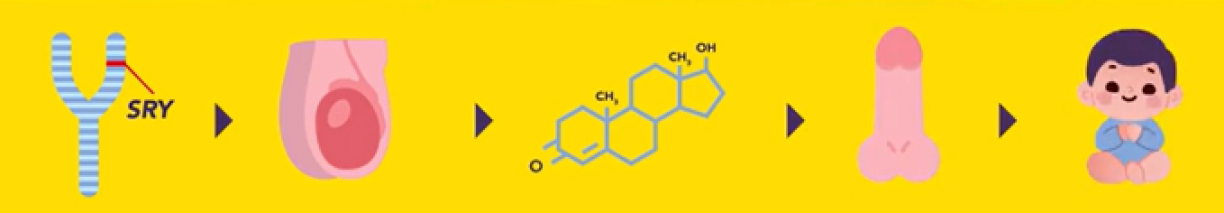

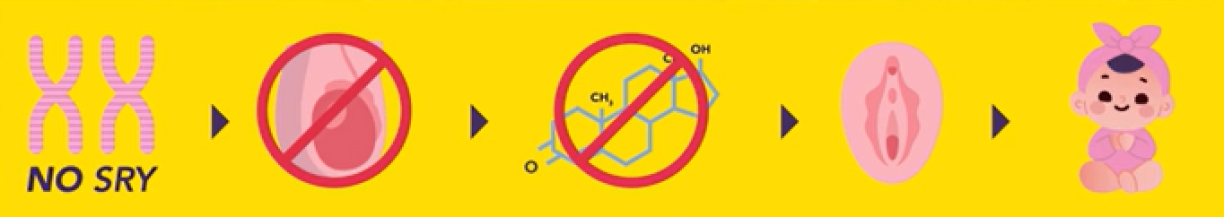

This is where a specific gene comes into play – the SRY gene, which is typically found on the Y chromosome (as you may recall,XX equals woman, XY equals man). So, this gene usually appears only in men. It causes the sex glands to develop into testicles. The testicular tissue then produces testosterone. This testosterone drives scrotum and penis development. Without the SRY gene, the glands form ovaries instead. Because there is also no testosterone, the vagina and vulva develop afterwards.

To recap:

These are the two primary pathways. However, deviations are possible.

For instance, the SRY gene can occur on an X chromosome. Then, someone chromosomally female can still develop testicular tissue and thus also male reproductive organs. Conversely, it is possible that a chromosomally male person lacks the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. This can result in reproductive organs developing in a more female pattern. In these cases, reproductive organs may develop ambiguously or exhibit both male and female traits (like a testicle on one side and an ovary on the other).

There are also variations at the hormonal level. Some people with XX chromosomes produce high testosterone and low oestrogen. And vice versa, some with XY chromosomes produce high oestrogen but low testosterone.

What we do know is that intersexuality is a relatively rare phenomenon. The United Nations estimates that approximately 0.05 to 1.7% of people are intersex. For Luxembourg, that’s roughly 300 to 11,000 individuals. Another statistic: At the CHL, an average of three intersex babies are born every year.

Historically, intersex babies were often simply assigned a sex at birth – often through surgical intervention. The assumption was that if you raised a person as a certain sex, they would eventually identify with that sex. Nowadays, we know that it’s not that simple and that intersex people often experience body discomfort and/or social rejection.

Because, for example, they realise that they align with the opposite of the sex that was assigned to them at birth. Or because it becomes obvious that they physically develop in the opposite direction during puberty. Or because they actually identify as intersex, i.e. neither strictly male nor female, which is also true biologically. Outwardly, intersex people may appear in various ways, either male, or female, or androgynous.

Nowadays, the consensus is that gender reassignment surgery should not be performed on intersex babies at birth, with a ‘wait-and-see’ approach being favoured. However, how this actually works in practice likely varies from case to case. Let’s now look at people who are biologically clearly either male or female, but who don’t identify that way. In such cases, we’re talking about gender identity. People in this situation are referred to as transgender. By the way, did you know that the ‘I’ in LGBTIQ+ stands for ‘intersex’?

So, what does all this mean? How many biological sexes are there? The vast majority of people are clearly male or female at a biological level. For practical reasons, it can therefore make sense to simply divide them into two categories.

By the way, this is something that is often done in science: creating simple models because they cover most cases. However, this doesn’t prevent us from acknowledging that reality is more complex. Whether you say there are mainly two sexes, or two sexes with a spectrum in between, or that there are three biological sexes, or whatever, is ultimately a matter of definition.

And it depends on the context. When treating patients with medication, for example, hormones are an important factor to consider. For various diseases, such as uterine cancer or testicular cancer, classifying patients by sex organs makes sense. In reproduction, it matters whether someone can produce sperm or egg cells, and so on. The fact is, however, that intersexuality exists – and biology is more complex than one might think.

And at this point, we have not even addressed gender identity, sexuality, and other aspects related to sex. So how should we deal with intersexuality now – at the administrative, linguistic, social, and interpersonal levels?

That’s a question for all of us, but also for society and politicians. However, science can show how complex the situation is.

Ziel mir keng! is broadcast on Sunday evenings after the programme Wëssensmagazin Pisa on RTL Tëlee and is a collaboration between RTL and the Luxembourg National Research Fund. You can also watch the episodes on RTL Play.

Author: Jean-Paul Bertemes (FNR)

Editing: Lucie Zeches, Joseph Rodesch, Linda Wampach, Michèle Weber (FNR) Kai Dürfeld (for scienceRELATIONS – Wissenschaftskommunikation) also contributed to the research work

Video: SKIN & FNR

Translation: Nadia Taouil (www.t9n.lu)