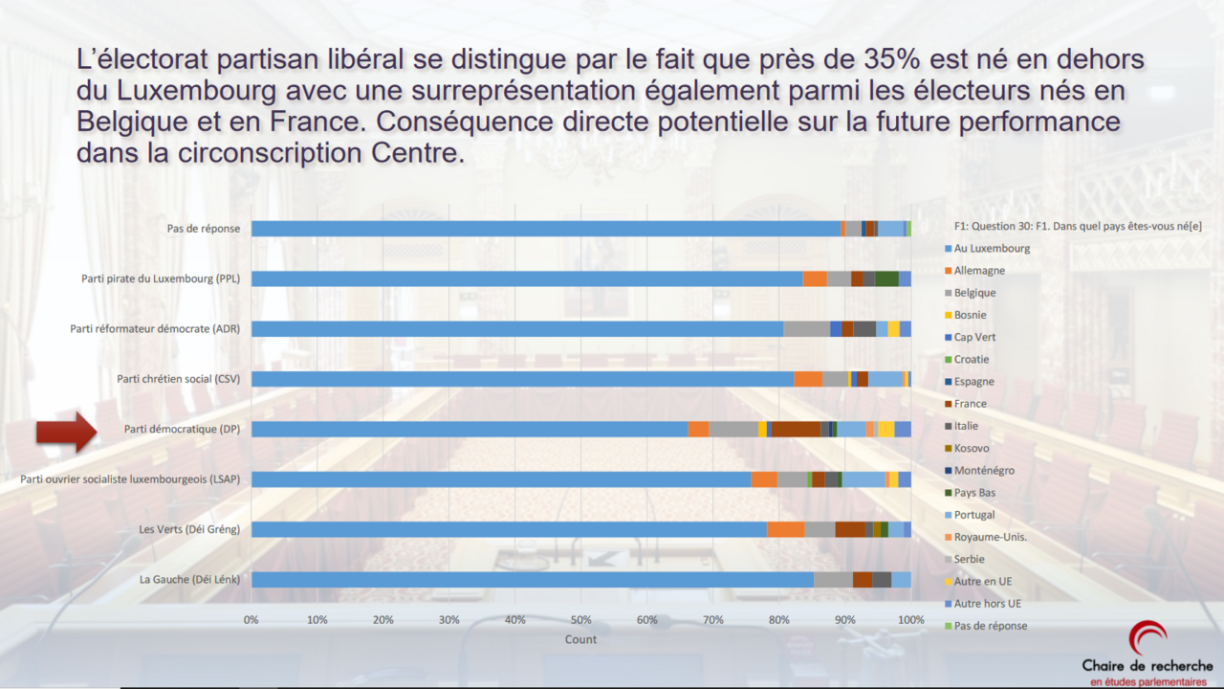

The answer appears to be a resounding “no.” The supporters of various political parties exhibit not only nuanced but often stark differences among themselves, at times surpassing the distinctions between the political parties themselves. One notable area of divergence pertains to the origin of voters.

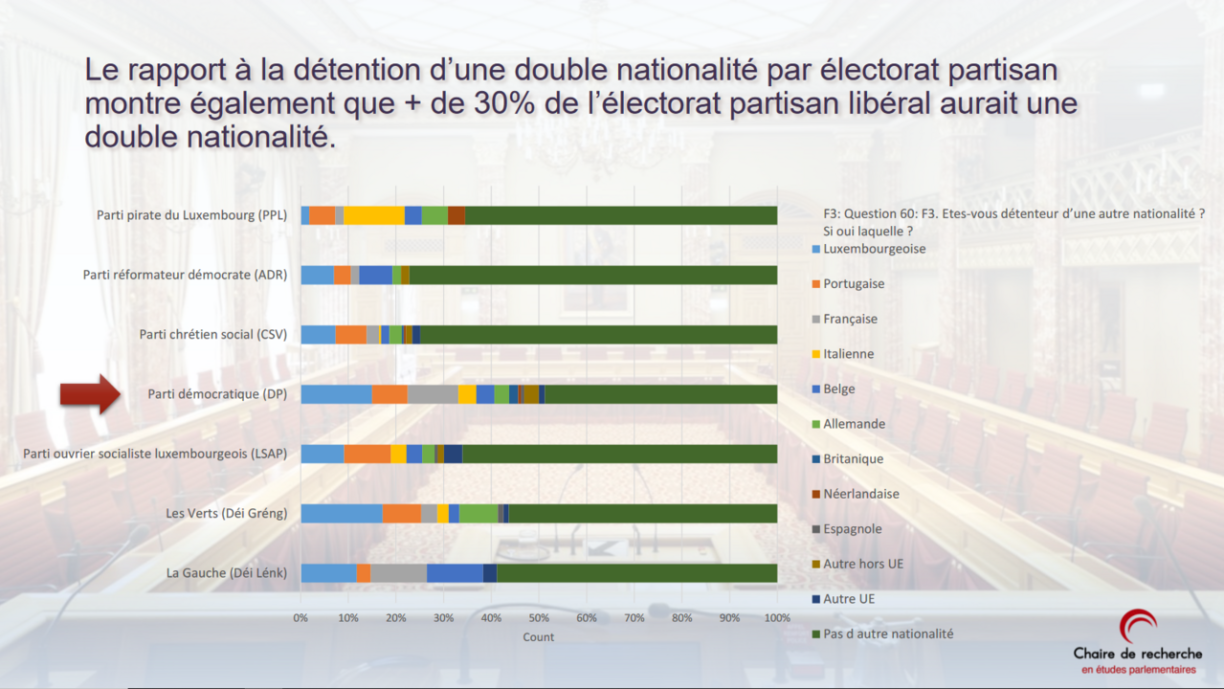

The Democratic Party (DP) stands out as the most internationally oriented, with nearly 35% of its supporters originating outside the Grand Duchy, and approximately 30% possessing dual nationality. A closer look reveals that individuals hailing from Belgium and France are notably overrepresented among those born abroad. Analysts speculate that this phenomenon might directly influence the DP’s performance in the Centre constituency. Conversely, the Pirate Party, the Left Party (déi Lénk), and the Christian Social People’s Party (CSV) have the highest percentage of voters born within Luxembourg’s borders.

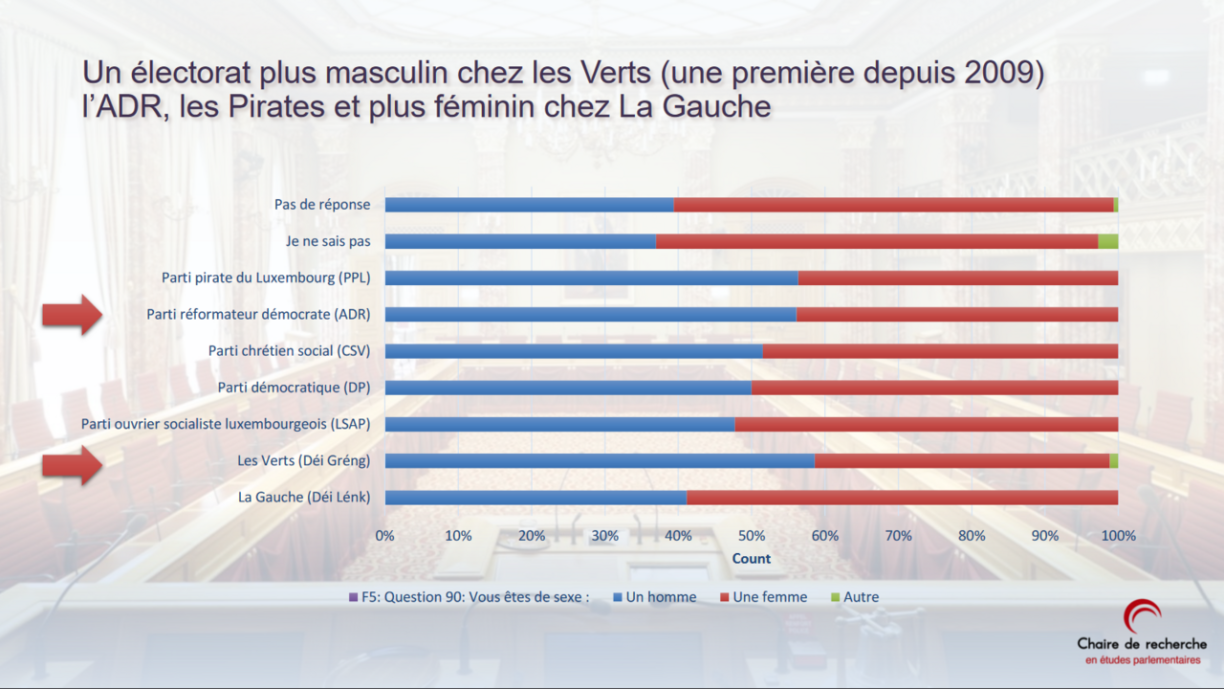

A gender-based breakdown also unveils intriguing patterns. The Green Party (déi Gréng), the Alternative Democratic Reform Party (adr), and the Pirate Party have a higher proportion of male supporters. This marks the first time since 2009 that the Green Party has garnered more male than female supporters. Notably, they are also the sole party with a segment of supporters identifying as non-binary. On the other end of the spectrum, the Left Party boasts the highest percentage of female supporters, with almost 60% of its allegiance coming from women.

The POLINDEX study also reveals some noteworthy shifts over the past few years, encompassing changes in voter types, economic perspectives, occupational diversity, and key issues driving political allegiance.

According to political scientist Philippe Poirier of the University of Luxembourg, there are three distinctive changes in particular. Foremost among these is the increasing presence of high-income voters since 2009. This development, particularly when compared to neighbouring nations, is “remarkable,” Poirier notes. While this development implies on the one hand a growing emphasis on economic concerns in the political discourse, Poirier also highlights the emergence of “social conservatism” or the “conservatism of well-being.”

“This means, for example, that we think of the environment not at a global level but of the environment in my neighbourhood; The environment means nature, safety, etc. in my neighbourhood,” Poirier explains.

Occupationally, Luxembourg has long been characterised by a substantial public sector workforce, relative to its population size. However, the dynamics are evolving, with a diversifying labour landscape. “The weight of the civil service and parapublic sector, while still significant, is gradually diminishing. This trend, observed twice since 1999, notably in 2018, could influence political dynamics, particularly in the Centre and South constituencies,” according to Poirier.

As a third pivotal shift, housing has gained further importance as an issue that drives voters’ choices. Voters increasingly tend to vote for parties based on how well they believe their candidates to be able to tackle the issue.

In addition, the study highlights Luxembourg citizens’ robust trust in their democratic institutions, though they are a good deal more sceptical regarding the European institutions. The ongoing secularisation could also have an impact on the electoral outcome.

The POLINDEX was conducted by the University of Luxembourg and the market research institute Ilres on behalf of the Chamber of Deputies.

Related