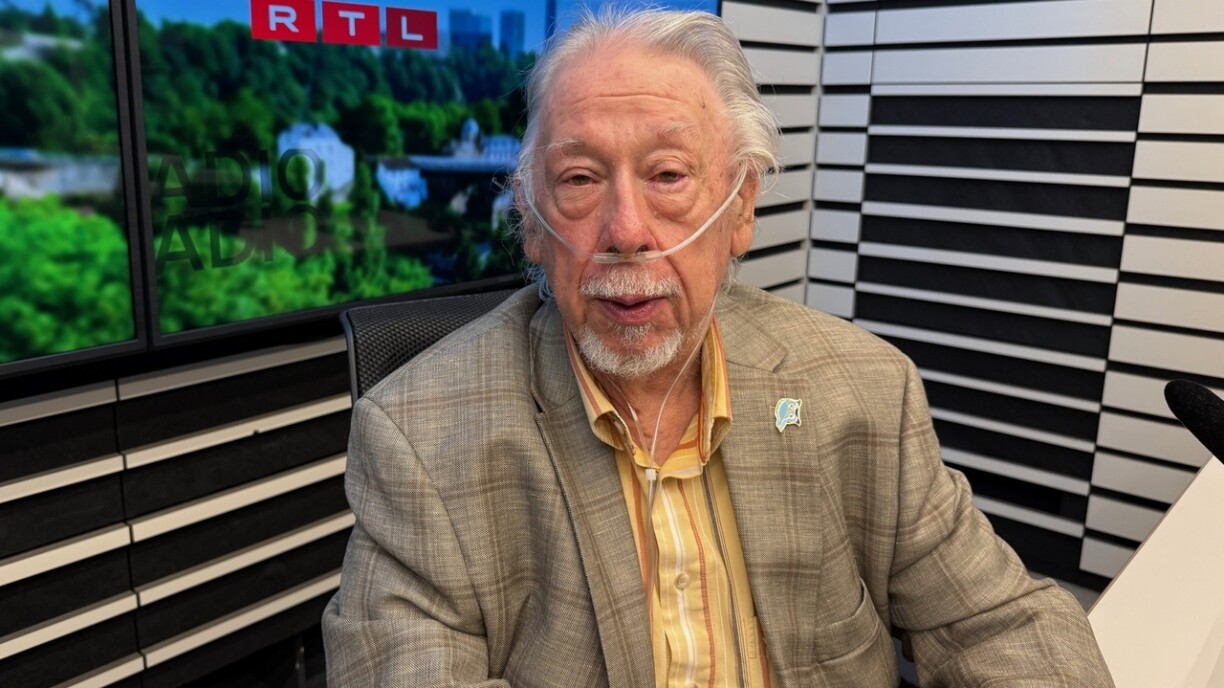

Bour, who has just published his second book on corruption in Luxembourg, stressed that although Luxembourg ranks fifth in Transparency International’s Global Corruption Perception Index, a good score does not mean the country is free of corruption.

He argued that cases do exist in Luxembourg, even if the problem often remains hidden. While official figures on investigations and convictions are known, he noted that in the past such cases could be counted on one hand, whereas now they appear in the press more frequently, involving both municipalities and ministries.

Bour explained that corruption is most likely where public funds cross into the private sector, including companies providing public services, even if they are not state-owned. He added that the law was tightened in 2001, so an act of corruption no longer requires proof that an illicit exchange actually took place – simply proposing or requesting an undue advantage is enough for it to be an offence.

Using examples from public procurement, he said it was worrying that in some cases officials responsible for buying on behalf of the state or a municipality might expect a percentage for themselves in return for awarding a contract. He also warned that corruption can take many forms beyond straightforward bribery, citing political party financing as a sector open to abuse, particularly where large donations may influence decisions without any explicit request.

While international evaluations, such as those by the Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the European Union have led to reforms in Luxembourg’s laws and parliamentary rules, Bour emphasised that gaps remain, especially at municipal level, which is now subject to review. He said part of the difficulty lies in the fact that not everything is perceived as corruption, as some acts are dismissed as harmless favours, and that there is often a reluctance to report wrongdoing, whether due to social ties or fear of consequences.

For Bour, raising awareness is essential, as is protecting whistleblowers, and ensuring that when prevention fails, offences are actually reported and prosecuted. A good ranking is positive, he stated, but he concluded that it proves nothing on its own and that vigilance is still needed.