The Luxembourg Esperanto Association, founded in 1971, serves as a hub for enthusiasts that gather every Wednesday. To the association’s president, Brian Moon, Esperanto is more than just a language, it also a movement and a series of ideals. “I met my wife through Esperanto,” he chuckles, “it has always been an everyday kind of language for me.”

Istvàn Ertl is one of them. Together with his family, he moved to Luxembourg in 2003 and speaks three languages: Hungarian, French, and Esperanto - the latter of which he learned given his professional involvement with the Global Esperanto Association. He believes that Esperanto makes for a much better universal language than English does, as it is politically and religiously neutral.

Other Esperanto speakers agree, arguing that it allows for equality (at least on a linguistic level) precisely because everyone has to put in an effort to learn it.

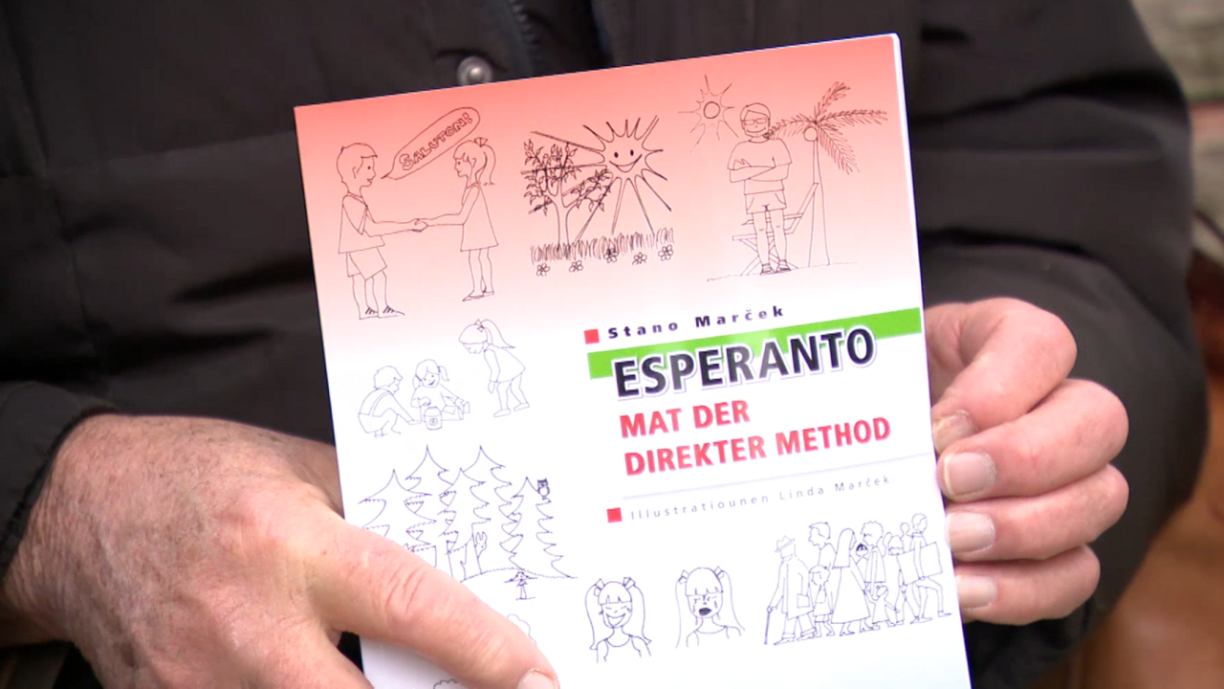

The language is often dubbed the simplest language in the world due to its straightforward structure. Its grammar consists of just 16 rules, all regular, and every word is pronounced as written, making it much simpler to learn compared to other languages. Moon adds that when he learned Esperanto as a 13-year-old, it was the first language he felt fully comfortable speaking.

Unfortunately, exact statistics of active Esperanto speakers don’t exist as no country has it as an official language. Estimated numbers lie between 100,000 and 2 million speakers.

Esperanto was created in 1887 by Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, who sought to establish a universal second language to foster global peace and a sense of community. By eradicating language barriers, Zamenhof sought to connect people worldwide.

At its peak in the early 20th century, Esperanto gained such momentum that plans were underway to establish an Esperanto-speaking state in Neutral Moresnet known as Amikejo - translating to ‘place of friendship’. However, plans were halted with the outbreak of World War I.

During World War II, Esperantists faced persecution; Zamenhof’s Jewish heritage and the international contact that many Esperanto advocates had made them targets of fascist oppression.

The dream of Esperanto’s universal adoption ultimately faded with the global rise of English as the dominant second language. And yet, the language has managed to establish itself in such a manner that some people learn it at a young age and consider it a mother tongue.

Despite its values and the relatively simple structure of the language, Esperanto faces criticism over its Eurocentric nature. Its pronunciation mirrors Italian, and its vocabulary and grammar draw from Germanic, Latin, and Slavic languages, making it a challenging language for non-European learners.

Equally, Esperanto’s male-dominated linguistic structure has raised concerns about sexism. Masculine forms are the default, with feminine denotations requiring additional word endings. For instance, patro means ‘father’, while patrino means ‘mother'; similarly, frato means ‘brother’ and fratino means ‘sister’.