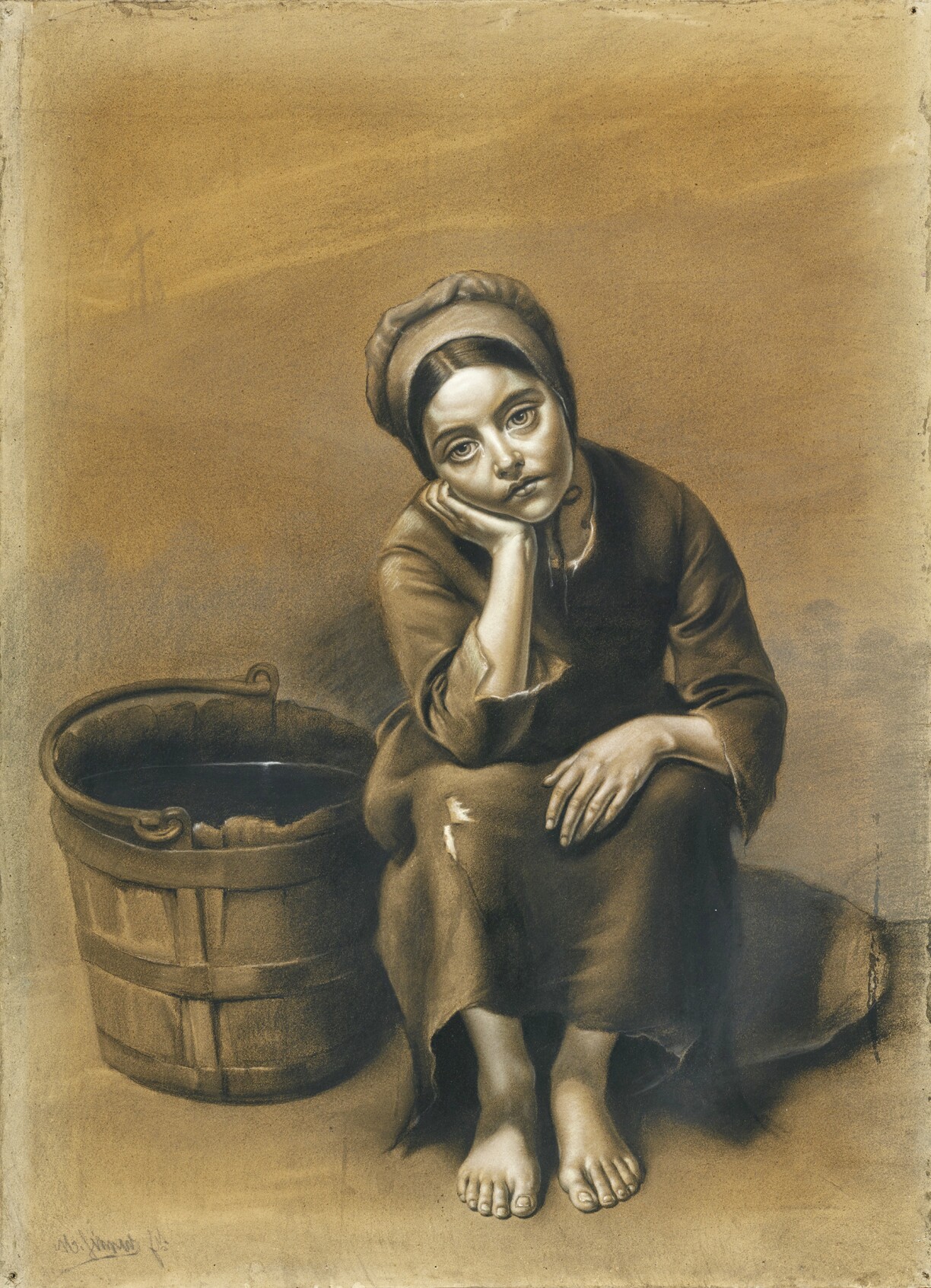

Not so long ago, extreme poverty in Luxembourg was represented by children, exploited in a most abject way. Recently, Luxembourg City mayor Lydie Polfer insinuated we could see a return to children being used to beg on the streets of the Grand Duchy.

It is necessary “to find a solution to prevent begging other than by coercion. The ban on begging does not make misery disappear; it merely prevents it from happening in public”. A comment which could easily be applied to the capital’s current issues with beggars; however, this particular phrase was printed in the “lndépendance Luxembourgeoise” newspaper on 11 February 1885. The debate on repressing the act of begging is certainly not new in Luxembourg.

In March this year, the municipal council in Luxembourg City decided to ban begging between 7am and 10pm in several of the city’s districts. According to the majority parties on the council, the DP and the CSV, the measure should target organised begging, rather than those who are genuinely in need. The president of homeless charity Stëmm vun der Strooss retorted that it was an “anti-poor” measure.

Minister of the Interior Taina Bofferding eventually ruled in favour of cancelling the measure, stating that begging did not represent a danger to the population. But the case is far from over, as Polfer has since signalled intentions to appeal the ministerial decision.

Begging in Luxembourg’s capital remains a thorny subject, with reports of aggression, theft, insults and exploitation of human misery. Some retailers expressed their frustration to RTL, describing the inconvenience of begging and claiming it was getting worse. But how bad is it really? A look back over Luxembourg’s history reveals far darker times in the late 19th century.

In the final years of the 19th century, begging was already considered “a true scourge”. “Even though it has been banned in virtually all countries, this ban is merely illusory. The begging continues,” wrote the Indépendance Luxembourgeoise on 11 April 1890.

“If it were just the infirm and the elderly who beg, unable to earn a living, we would hardly find fault with this practice, but unfortunately these days begging has become an art. They use every means possible to extract sympathy from the public and to extort money. Admittedly, it is not as bad as in Paris and other big cities, but the progress has been made,” continued the article from the now-defunct* paper, in alarmist discourse which has hardly aged today.

However, the article then goes on to describe a far worse form of widespread begging - that of children. “At the municipal council, the police were asked to keep an eye on those who exploit children, sending them to bars to sell flowers. In general, it could not hurt to carry out surveillance on beggars and vagabonds, particularly where children are involved. These children are initiated into this degrading trade far too early and if order is not kept, they will become professional beggars, the worst of professions.”

In order to push their point, the article’s author invited readers to look at begging practices in Paris. The observation is chilling:

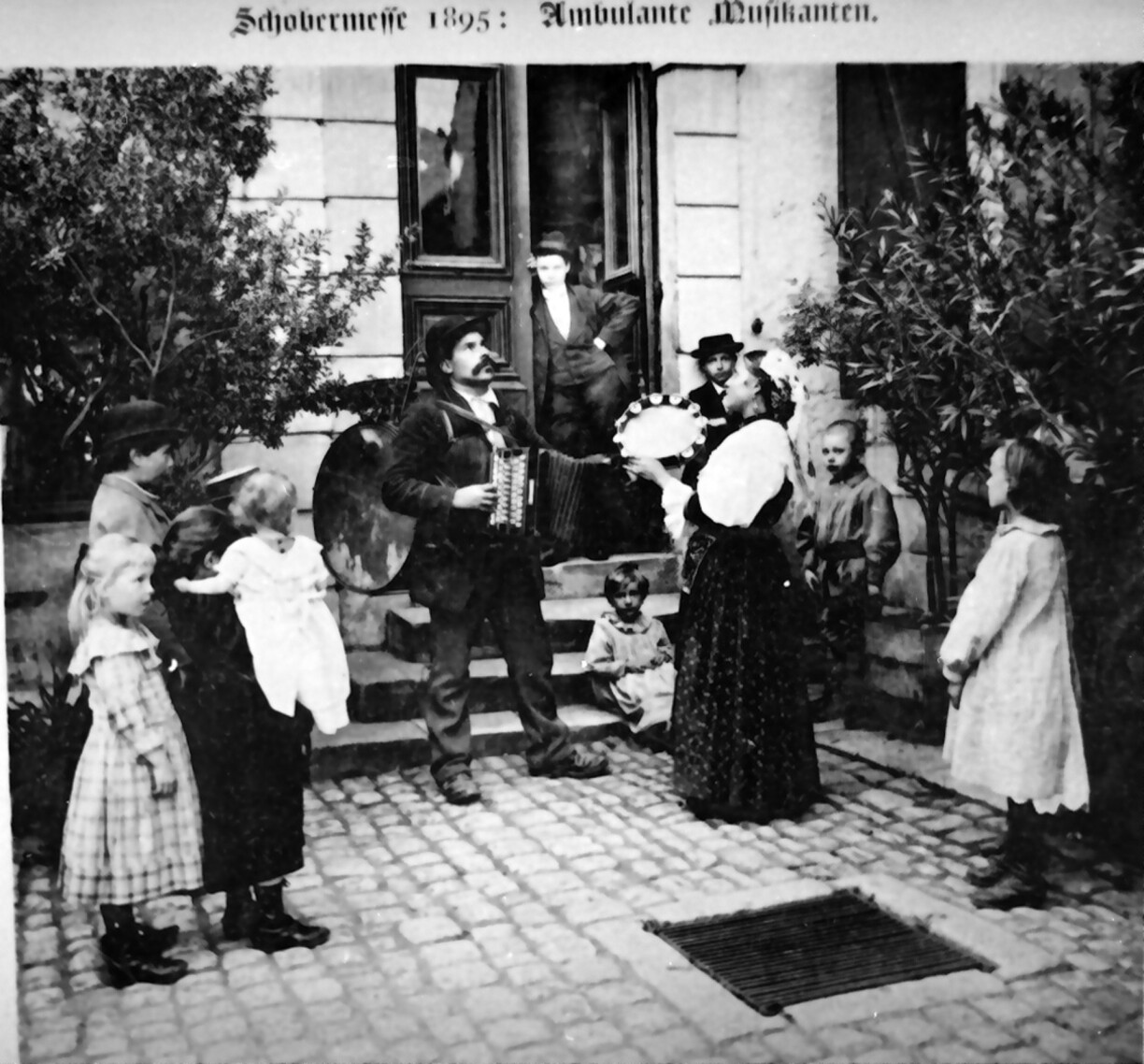

“The child is what most attracts the pity of charitable souls. Consequently, in Paris, there is a very large trade of children, who are not sold, but rented out by the day or night. If the child is old enough to walk, they are sent to busy areas, public places, church porches. By the evening they must bring back sufficient donations. Woe to the poor child if they have not reached the correct amount, as they will be badly beaten for their failures.”

These child beggars were divided into four categories:

By 1889, there were more than 3,000 of these “rented” children, ranging from one franc per day for a child in a vest, to five francs for the flower sellers and the musicians. The article evokes both the mortality for the children exposed to all conditions, as well as the “immorality”, with many young girls moving on to earn money away from music and flower-selling - in other words, prostitution.

The article does not specify whether child begging reached these extremes in the Grand Duchy; however, it is certain that child beggars were rife, and that the practice agitated the residents of the capital.

In another excerpt from 1 July 1889, the newspaper continues: “The public complains bitterly about the little vendors selling bouquets of roses, roaming the streets and cafés from 10 in the morning to midnight. It is begging, pure and simple. These young children, aged between four and ten, are watched by an older child, around 15, who waits outside the cafés for them to come out. If the children have not sold anything, they are subjected to beatings. On Place d’Armes, a woman was seen brutally hitting her child for not selling enough bouquets. Isn’t it time to end this exploitation of small children?”

The practice did not end in the 19th century, however; an issue of the Land newspaper dated 25 December 1959 complained that Luxembourg’s medical inspectors and social workers “discover more cases every week of children in moral danger, who are unhappy and exposed to begging, prostitution, vagrancy and delinquency.”

Although the issue of begging is clearly a hot topic in the capital today, the country has come a long way since masses of children roamed the streets, largely due to the introduction and compulsory schooling, as well as Luxembourg’s economic expansion. But the risk has not been fully eradicated. Luxembourg City mayor Lydie Polfer recently mentioned that child beggars had returned to the capital, calling it a “real market” for organised human trafficking.

Poverty is also on the rise, affecting more families in the Grand Duchy, and by extension, more children. A national survey by the NGO ECPAT Luxembourg made reference to several recent cases of “sexual exploitation of children for the purposes of prostitution, reported by child protection professionals”, giving rise to Polfer’s concerns.

*Editor Jean Joris published the first edition of the Indépendance Luxembourgeoise on 1 October 1871. The French-language newspaper appeared until its final publication on 31 December 1934.