Pentecost can sometimes seem like a “second grade” holiday. Most people do not know what it is about exactly, and even some Christians are not quite sure what it is that they are supposed to be celebrating. In contrast to Christmas or even Easter, Pentecost has also not really entered the mainstream and as such, a lot of people do not think about it too much and are simply glad to get some time off.

However, Pentecost used to be quite an eventful period of time in the past, and not only for religious reasons. There is of course Echternach’s dancing or hopping procession, which usually takes place every Whit Tuesday and has, over the many years of its history, become one of the country’s big national events. As it is still very popular and well-known, this historic tradition will not be discussed in this article, but if you are interested you can find out more about it here.

This article will instead focus on another Luxembourgish tradition that used to take place around Pentecost but has been completely lost over the years.

The Wëllemannsspill (“wild man play”) was a somewhat more unusual Pentecost tradition. Almost completely forgotten today, it once enjoyed great popularity and was described on numerous occasions, including by one of Luxembourg’s most famous writers, Edmond de la Fontaine, better known by his nickname Dicks, a fact which unfortunately ensures that he will never be taken seriously by Anglophones (the statement Oh by the way, this play was written by Dicks will simply never not be followed by immature giggling).

In his excellent book De Sproochmates II, Alain Atten gives a detailed description of how the event went down in Grevenmacher:

The younger men of the village came together and covered one individual in all sorts of foliage and leaves. They then led him on a chain through the village. The “captors” purposefully let this “wild man” escape again and again, so that every alleyway got their fair share of the fun. At the end, the foliage was gathered and burned.

However, the same group of men also did something else as part of this tradition: they rounded up as many older bachelorettes as they could, tied them up, put them in a sort of trolley, and brought them out on to a field outside the village. Atten adds that it is unknown whether they were then brought back or had to walk back into town themselves.

There are a few interpretations regarding the meaning of this custom. One perspective is to see the wild man as part of a wide variety of end-of-winter/beginning-of-summer traditions that can be found in numerous folklore customs across Europe. In this context, the “wild man” acts as a personification of winter. Despite “escaping” a number of times, the frosty season ultimately always has to give way to the arriving summer.

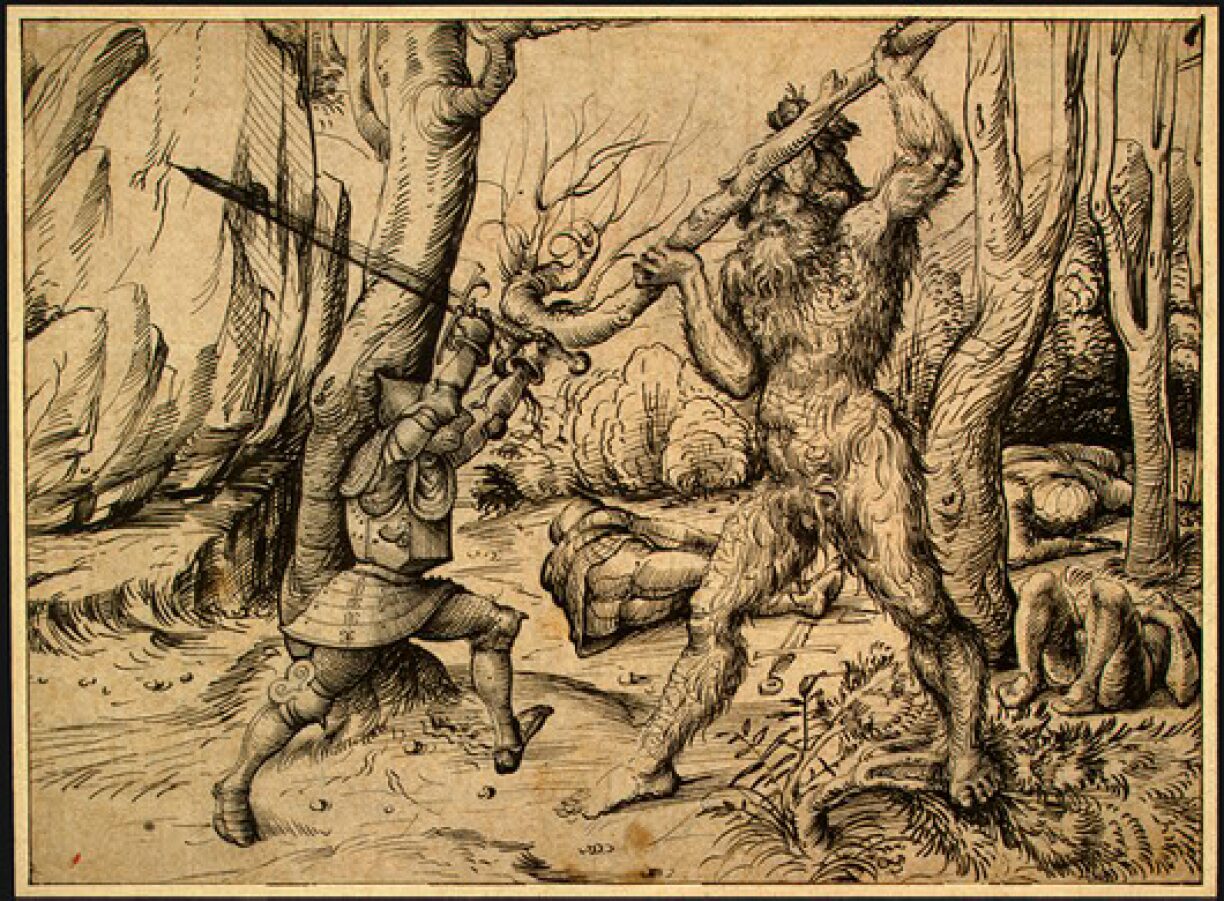

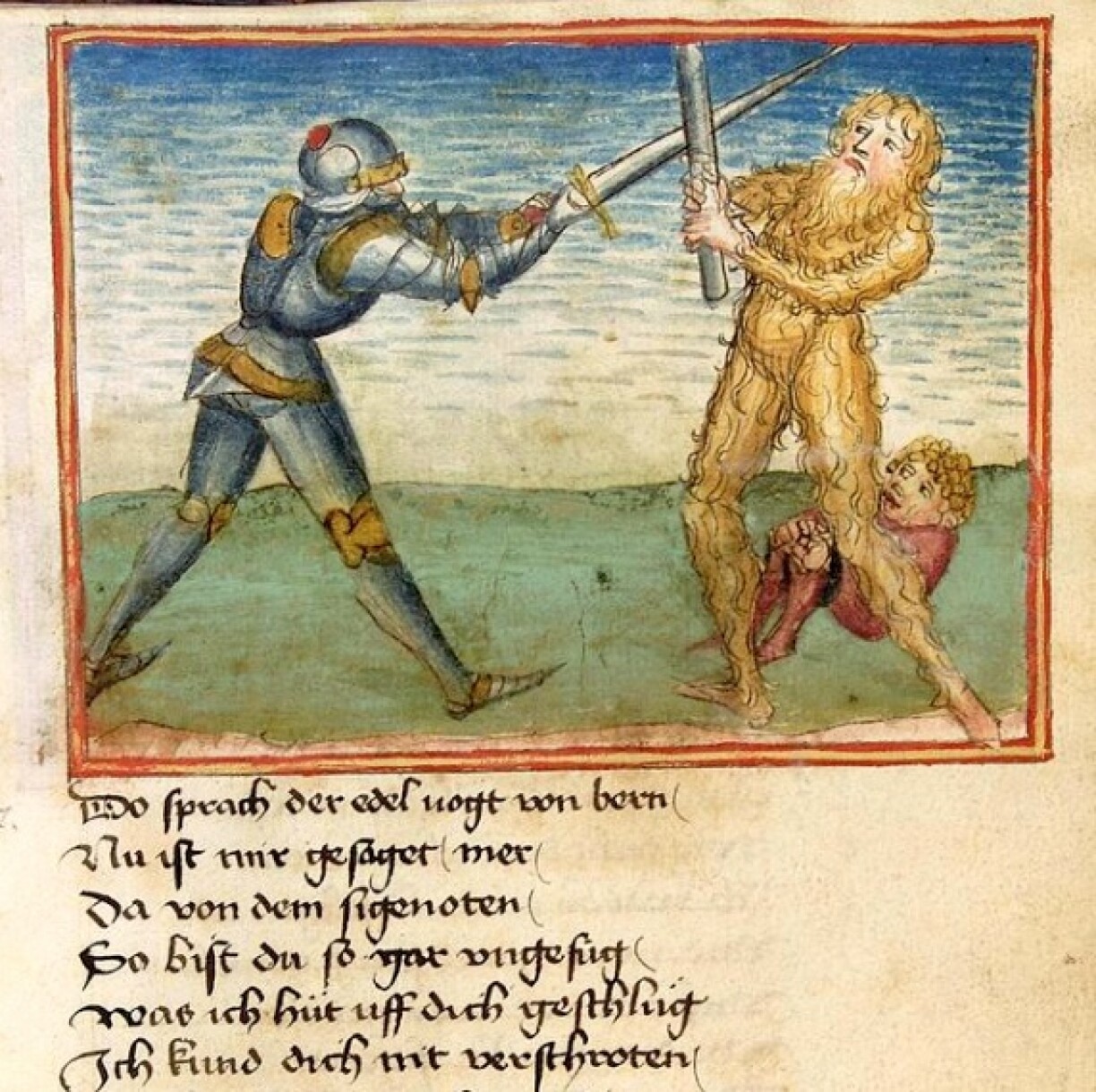

Another interpretation is a bit more moralistic. The “wild man” is a very common trope in European folklore, particularly in Germanic and Slavic folklore. In his article on the wild man tradition in the Swiss canton of Valais, David Pfammatter notes that the wild men “behave contrary to social norms and symbolise an anarchic, pagan-primitive way of life.” As a “malicious and immoral figure who is in league with the devil,” they are meant to serve as a contrast to the innate moral goodness of the Christian faith.

Pfammatter also highlights that in the case of the Swiss tradition, the wild man fulfilled the role of a scapegoat. During the plays in Valais, the wild man is put on trial and symbolically charged with all of the bad things that have happened in the village over the past year.

As for the stranded bachelorettes, Atten points out that this tradition also existed in Germany and Switzerland and is also the origin of the phrase “Die Jungfern werden ins Moos gefahren” (lit: The maidens are driven into the moss).

While this tradition certainly appears to have been most prevalent across the Moselle region, a very similar tradition existed in northern Luxembourg, in particular in what used to be the County of Wiltz. In Bavigne, a man was covered in foliage and a variety of common winter plants and then taken for a ride across the County. According to Atten, tradition required for instance that he be welcomed by the mayor of Kaundorf. Interestingly, the man actually had to be escorted by the county’s armed men for his own protection. Up north, he was known as the Päischttopert (Pentecost Fool), and as Atten puts it: "[…] as for how they treated a fool back in the day, we can spare ourselves the details.”

In nearby Arlon, the tradition also existed and regularly led to outright street fights. While the local court refused to get involved, the brawls got so out of hand that the provincial council ultimately had to intervene.

So, while Pentecost may appear quite bland and boring to us nowadays, it actually used to be a rather busy time of year in the past. Did you also know that the pretzel swapping on Bretzelsonndeg used to be part of a much more elaborate tradition that included another pastry swap around Pentecost? You can find out more in our Pretzel Sunday deep-dive!

And if your thirst for local folklore still has not been quenched, you may want to check out our Literary Legends series, in which we explore the misty woods of Luxembourg’s most harrowing folk tales:

The moor spirit that haunts the woods near Moutfort

Wolfin’ around: Werewolf tales from across the Grand Duchy

The spirits that haunt drunkards

Tales of Luxembourgish witches and wizards

Thieves’ Lights – Luxembourg’s dark twist on an eerie legend

Grieselmännchen – The sinister tale of Luxembourg’s Black Knight

Betrayed lovers and cursed counts: Four ghost stories from the Grand Duchy

Will-o'-the-Wisps – Beware of trickster fairies on Luxembourg’s hiking trails!

Who you gonna call? Luxembourg’s magical priests, of course!

Jasmännchen – A spirit and its epic showdown with a local super hermit