Over the past few weeks, we’ve covered the rulers of Luxembourg, from the first Count, Siegfried, in 963, to the last Duke, Francis, in 1795.

We’ve also explained the complex geopolitical situation that saw the House of Luxembourg rise to the top, while the Duchy became engulfed in constant wars for centuries.

Today, we’re diving deep into the domestic affairs of Luxembourg, to explore how it was governed, and what life was really like in Luxembourg before it was a Grand Duchy.

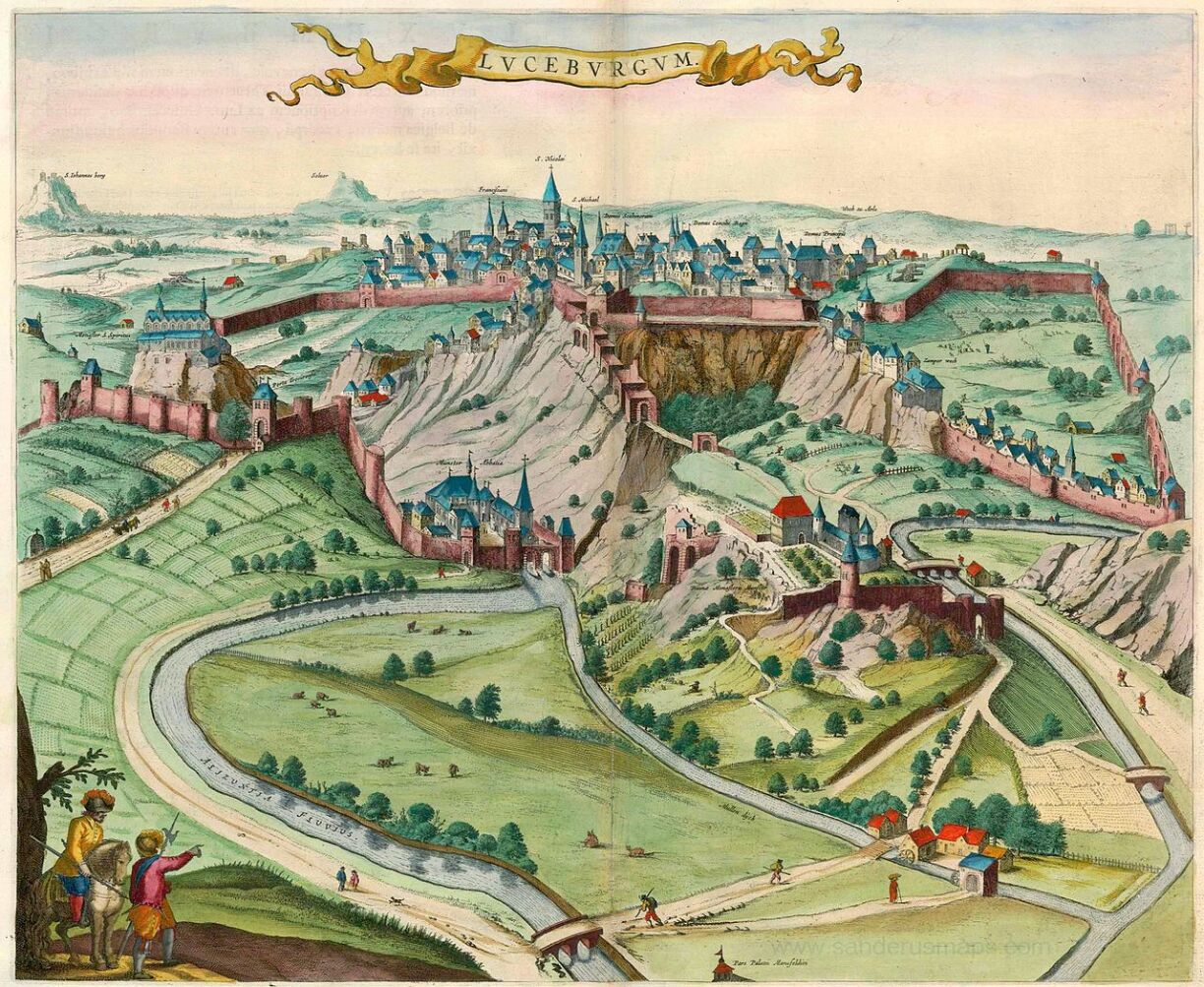

After the founding of Luxembourg in 963, a town started to grow around the castle.

Over the next few centuries, merchants, artisans and peasants began to settle in the area, founding religious institutions such as St Michael’s Church, while monasteries were set up in the surrounding areas.

The early County of Luxembourg, which steadily acquired more and more territory from neighbouring polities, was initially marked by seigneurial relations between the ruler and his vassals, but things changed in the 1230s under the reign of Ermesinde.

She introduced the first known charter of freedom to the inhabitants of the city, and introduced administrative and judicial bodies such as a council of advisers, made up of the most important noble families in the County.

Ermesinde and her son Henry V, through good governance at home, in effect set a platform for their descendants to rise to the top of the Holy Roman Empire

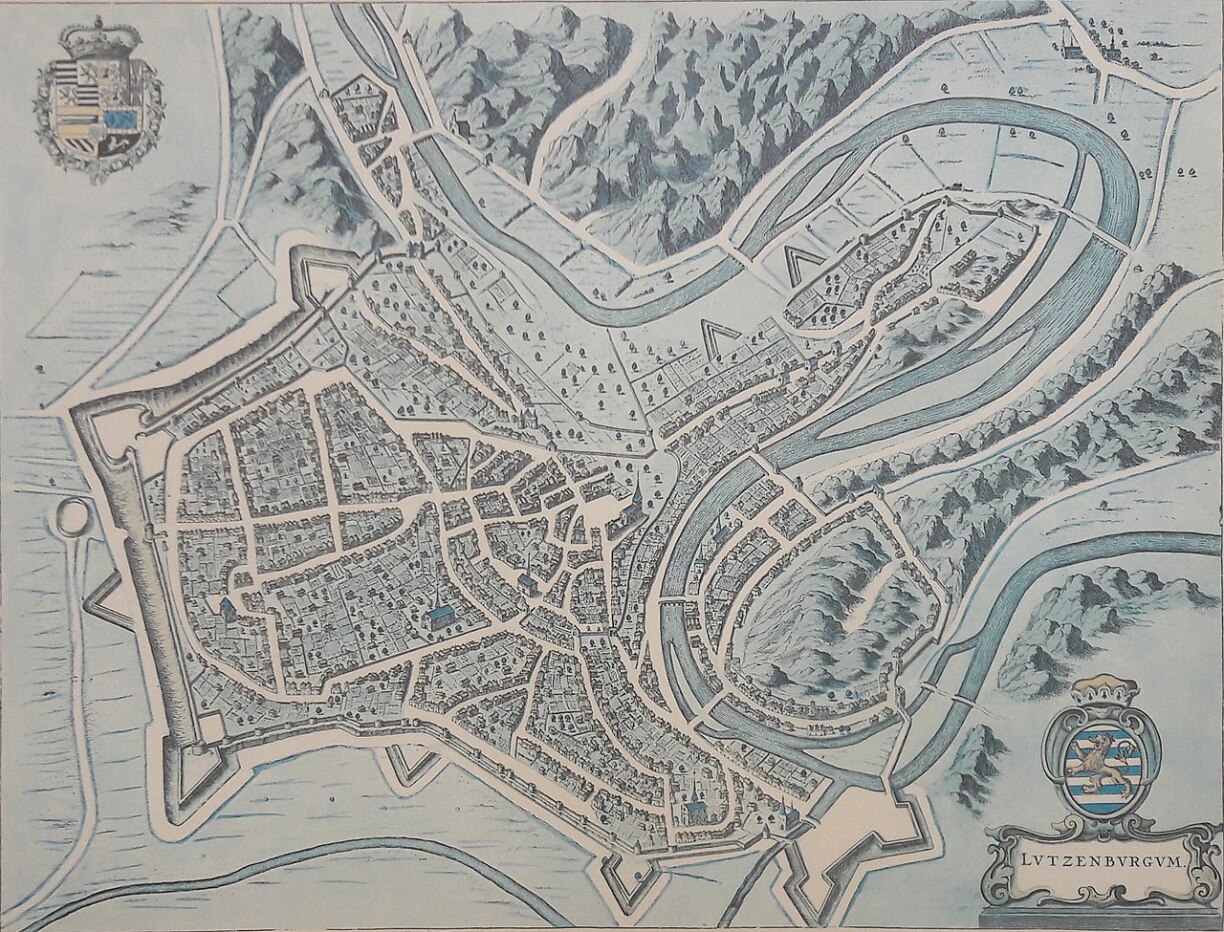

Meanwhile, the fortress of Luxembourg was in constant evolution, being fortified further by practically every Count over the years.

And the stronger the walls of the town became, the more confidence merchants and artisans had in living there, creating a new bourgeois class in Luxembourg.

But the County of Luxembourg, then as now, was a border region, divided in a number of ways.

There was an increasing separation between the growing town of Luxembourg, and the countryside outside of it.

The counts’ acquisition of lands in modern-day Belgium and France (Arlon, Thionville, Bastogne) led to the spread of French culture and language into the town of Luxembourg, but the rural eastern parts of the Duchy remained firmly German in orientation.

Religiously, the territory was also divided between a number of authorities, from Liège to Trier and Metz, while churches continued to go up in Luxembourg itself, such as the Münster Abbey.

And the County likewise suffered from a difficult geography, split in two by the Ardennes forest and lacking in navigable rivers other than the Moselle.

This combination of factors ensured that Luxembourg remained a bit of a backwater throughout the Middle Ages: a rural, under-developed, feudal and highly religious society.

The rise of the House of Luxembourg in the period 1308-1437 led to the development of an early modern system of administration and taxation in Luxembourg.

The 5,000 or so merchants and artisans living in the town of Luxembourg – millers, brewers, tanners or weavers – grouped together to form corporations and guilds, effectively organising themselves into political bodies who could exercise collective power.

To finance their elections through bribes and fight long wars across Europe, the rulers of Luxembourg had to raise money by bartering with the increasing power of the bourgeoisie, who in exchange were granted a number of privileges and freedoms.

These could be economic, such as exemptions from forced labour or from extraordinary taxes and the right to mint coins and collect tolls.

They could also be political - the right to elect a mayor and councillors, or judicial protections.

Under Henry VII and John the Blind, the County of Luxembourg began to seem a coherent territorial unit, with fortified towns and castles all around the central fortress in Luxembourg.

And, for the first time under Wenceslaus I in the late 14th century, an Assembly of Estates was called to authorize new taxes.

This Assembly of Estates would last on and off until the end of the Duchy in 1795, and it was comprised of the three estates: nobility, clergy, and the Third Estate.

The Estates of Luxembourg quickly became so powerful that after Philip of Burgundy captured the town in 1443, it was empowered to legally recognise him as the sovereign Duke of Luxembourg in 1461.

As part of the Estates’ recognition of Philip, he in turn promised to respect the ancient rights and liberties of the city, its administrative councils and its local institutions.

For the next centuries, through Burgundian and Habsburg rule, Luxembourg would be governed by three principal institutions.

The Assembly of Estates dealt with taxes and politics; the Provincial Council of nobles dealt with justice, religious matters and administration in the countryside; and the governor, appointed by the largely absent Dukes, was in charge of military matters and raising taxes.

The governor was usually foreign, with some exceptions - Jean Beck and Jean Frédéric d’Autel were both Luxembourgish, while Peter Ernst von Mansfeld was governor for so long that he basically became a local, even building himself a massive castle in Clausen.

Meanwhile, as one of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands, Luxembourg was also represented at the Estates General in Brussels or Bruges, but these stopped meeting after 1632.

However, it remained quite distinct from the rest of the Netherlands, both before and after the Dutch Revolt, due to its geographical distance from Brussels, its poor transport links, and its lack of important centres of trade.

Sadly, Luxembourg just wasn’t that exciting a place to live under the Spanish Habsburgs.

By the 17th century, the town of Luxembourg had 13 guilds to Brussels’ 52, and a population of 5,000 to Brussels’ 100,000.

It had no cultural Renaissance to speak of, and the printing press only reached the Duchy in 1598.

There was no religious awakening either: the Jesuits arrived in the late 1590s, preventing the spread of Protestantism, and leading to the renewed construction of churches such as the Neumünster and the Notre Dame cathedral.

It was by and large the same agricultural society that had existed since Ermesinde’s rule, and things would not get better in the 17th century.

As we have previously seen, the Franco-Habsburg rivalry led to wars and famines that devastated the population of the Duchy of Luxembourg right up until 1714.

Only with the rule of the Austrian Habsburgs would the Duchy return to prosperity.