If you are looking for silk stockings in Luxembourg, we see that in 1671 they were taxed by the pair at 7 florins 10 solz. In comparison, stockings made of Sayette (a lightweight wool) were taxed by the dozen at 17 florins 10 solz. Women’s and children’s stockings were taxed less than men’s items.

Taxes provide insight into the affordability of goods. Common stockings made of linen or wool in Luxembourg are not mentioned, likely because they were not taxed. Luxembourg seemed to keep common goods tax-free and preferred to heavily tax luxury items. Taxes were recorded in florins, solz (solidus), and denarii, which also reveal the flow of imports and possibly black market items.

In 17th-century Luxembourg, the economy was characterised by the use of florins, solz, and aulnes for trade and taxation. Florins, derived from a widely recognised gold coin, were used for high-value transactions and luxury taxes. Solz, stemming from the Roman solidus, were smaller denominations for everyday transactions.

Lace made of gold or silver thread was taxed at 60 florins per pound of 16 ounces, while silk lace was 40 florins per pound, and faux gold or silver lace was 15 florins. Linen lace, the most common type, was not taxed.

Buttons made of gold or silver thread were taxed by the pound and were the most expensive. Buttons made of golden silk threads or regular silk were half the price. Fashionable buttons made from camelhair thread had a significantly lower tax, making them affordable for the average person. Buttons made of other materials, such as bone, tin, or pewter, also appear not to have been taxed.

For fine linens from Holland, a person paid 150 florins for one piece (40 aulnes in length). For the same tax, one could get 5 pounds of gold thread buttons or about 2.5 pounds of gold lace. One piece of Holland linen could make a few pairs of very fine bedsheets or several shirts. Linen from Liège, which was slightly thicker but still very good quality, was taxed at 75 florins, whether it was 40 or 45 aulnes in length. At this time, fine linen was competing with gold.

According to the 1671 edict, aulnes were measured by the foot, following the Antwerp measure. Lengths measured in feet with a remnant used Ghent thumbs (similar to inches). Valuations were in florins, and the tax was stated in solz, derived from the Roman solidus. Other weights and measures followed common practices in the Benelux region.

The 1671 tax list seems to be the first time textiles and clothing were taxed, while products like wine had been taxed since the inception of taxation.

In 1738, Joseph Michel Wouters compiled copies of all placards from the 17th and early 18th centuries and published them in a book, vol. 8, published by George Fricx. Originally, placards were published as leaflets, making them difficult to use as references.

Early Luxembourgish placards from the 16th century were published in Latin and Flemish, while those from the first half of the Silver Age were published in German. Placards in French were introduced around the 1640s, though there is some debate about this.

The placards of Luxembourg show that while Luxembourg was not a major trading city like Holland or Venice, it was regionally significant.

For instance, the placard of June 27, 1671, removed all taxes on goods except those listed in the Placard of Haut-conduit, February 1623. It also stated that the entrance/exit between Luxembourg and Trier would be lowered or abolished, including those for wines, potentially leading to free trade between the two estates.

Wines from France, Metz, Lorraine, and Bar, purchased for personal use or at wholesale, were taxed at 15 florins per hotte de vin when brought into Luxembourg. This tax would reduce wine imports from French-speaking regions but did not make acquiring such wines prohibitive.

Sheep from Germany were taxed at only 2 florins per animal, which might explain why the reddish Luxembourgish sheep resembles the red Coburg Fox Sheep from Germany. This also highlights an interesting point: working-class or peasant clothing was often of natural colours. Most local sheep produced white or black wool, but the presence of red sheep also yielded cream wool from the belly and brick-red wool from the chest.

Merchants from Liège to Luxembourg and then Germany paid 2% of the value as tax. Merchants from Liège, Stavelot, Juliers, and Aix who travelled to Luxembourg and then into France also paid 2% of the value upon entering the Duchy, except for copper, which was taxed at only 1%. Merchants arriving by the Moselle paid no tax.

It is notable that a 2% tax generated enough revenue to build castles, maintain armies, and purchase cannons during the Silver Age. Today, it is challenging to imagine such a low 2% sales tax on general goods, but New York State, with a 4% sales tax and zero taxes on food and medical products, demonstrates that such tax rates can support significant public services.

Luxembourg did not only trade with France, Belgium, and Germany. Goods travelled from the Netherlands through Luxembourg to Switzerland. In 1671, another edict, “Placcaert raeckend de Baenen ends Stricken van d’inne-komen Der Wine too with Las roode,” aimed to curb the illegal wine trade from the Netherlands to Luxembourg’s province, including Remich, St. Vith, Porcheresse, Neufchâteau, and Arlon. This was likely not the only smuggled item, but wine was the primary focus of the Duke’s efforts.

The journey to Holland was routine, with merchandise leaving Luxembourg via the River Our to the River Meuse and then to Holland, bypassing Liège. A duty was paid upon leaving Luxembourg, and this tax was deducted from the duty in Holland.

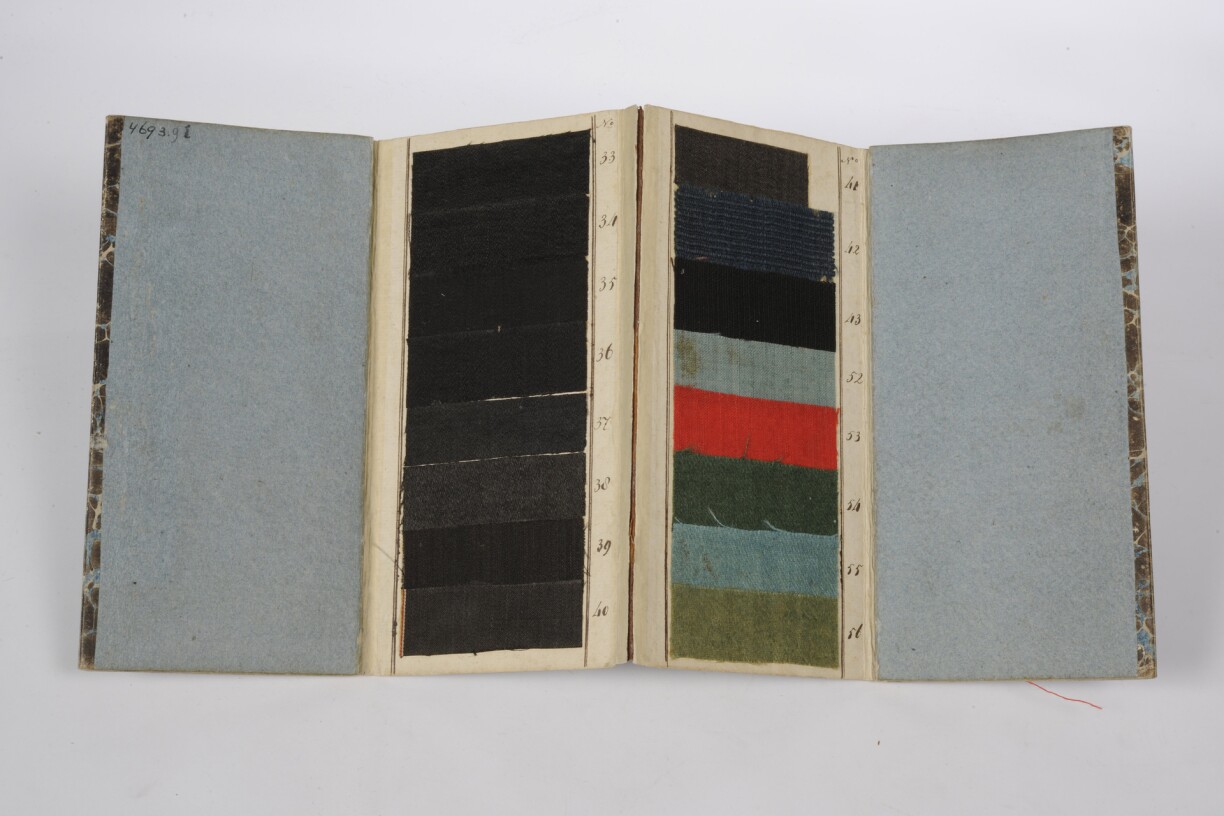

An edict section aimed to control various fabrics entering Luxembourg, including drapes, petite fabrics, wool or wool thread fabrics, serge, say, and Sayette, which required a seal at Luxembourg’s entrance. Fabrics were sorted by value: 100 florins or more were taxed at six solz, 50-100 florins at 3 solz, 25-50 florins at 2 solz, and less than 25 florins at 1 solz. Fabrics from France were taxed by length.

Fabrics such as Rasses, Cordelieres, and Serge de Chalon were 21 aulnes long if made in France but 35 aulnes long in other countries. The Duke set the tax at 35 florins for each length, making the shorter French fabrics less attractive. Rasses (or Russels) were a type of damask made from worsted wool, available in solid colours, two colours, or brocade. Cordelieres were corduroy, and Serge was a durable twill fabric. These fabrics were taxed regardless of their value.

Thus, a lightweight wool serge from the Netherlands could have a maximum tax of 6 solz, while a serge from France faced a 35 florins tax.

Shortly after, the King of France invaded Luxembourg. Blocking textile (and wine) trade from France likely caused frustration, but the blockage of iron bars might have been the tipping point. Luxembourg was renowned for producing high-grade iron for military cannons and was also noted for its liquors and butter.

Although Luxembourg produced textiles, they did not compete at the top level, which may explain why the Duke kept taxes low on common textiles like serge from Holland, which were attractive and durable.

About the author: Tara Mancini is an author with Buffalo Raising Journal. Articles have covered topic categories such as culture, charitable fundraisers, and city and State infrastructure since 2016. Mancini’s hobbies includes reading and collecting data from 17th century documents, then inputing the data into a database using spreadsheets for use in her articles.